Finding Your Roots

Hidden Kin

Season 9 Episode 1 | 52m 9sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

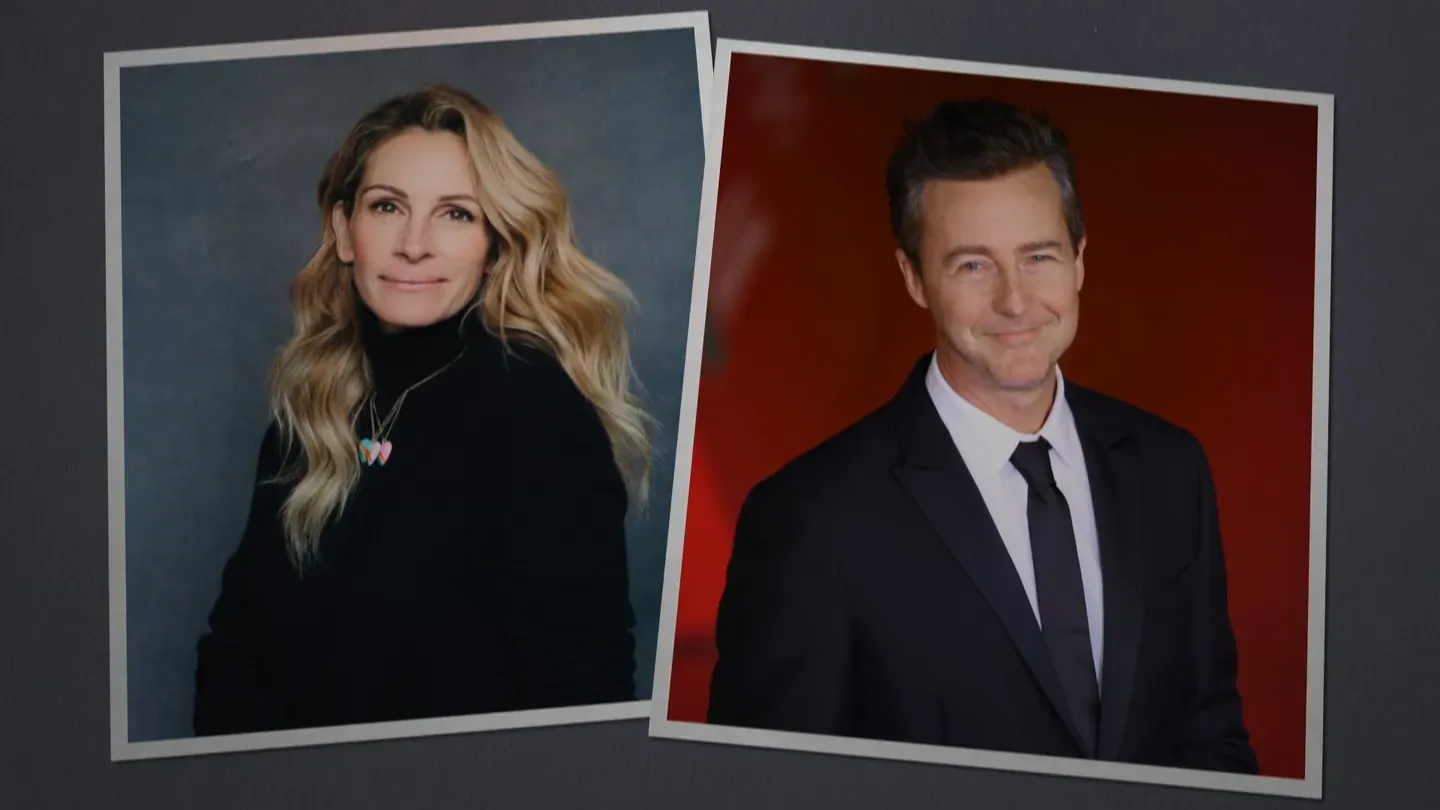

We explore Edward Norton and Julia Roberts' roots, revealing their hidden connections.

Henry Louis Gates explores the remarkable roots of actors Edward Norton and Julia Roberts—using DNA analysis and genealogical detective work to travel generations into the past, tracing lineages that run from Northern Europe to the American South. Along the way, Norton and Roberts reimagine their family stories and discover their hidden connections to our nation’s history—and each other.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Hidden Kin

Season 9 Episode 1 | 52m 9sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Henry Louis Gates explores the remarkable roots of actors Edward Norton and Julia Roberts—using DNA analysis and genealogical detective work to travel generations into the past, tracing lineages that run from Northern Europe to the American South. Along the way, Norton and Roberts reimagine their family stories and discover their hidden connections to our nation’s history—and each other.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGATES: I'm Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Welcome to Finding Your Roots.

In this episode, we'll meet actors Julia Roberts and Edward Norton.

Two stars who are about to be recast by their family trees.

ROBERTS: But, oh, wait, but am I not a Roberts?

GATES: Well, let's see what we found.

ROBERTS: This was a very unexpected turn, Doctor.

(laughs).

NORTON: It's wild.

These are consequential, these are consequential things.

GATES: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool available.

Genealogists combed through the paper trail their ancestors left behind, while DNA experts utilized the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets hundreds of years old.

And we've compiled everything into a book of life.

A record of all of our discoveries.

ROBERTS: This has got some heft to it.

GATES: What do you think of that?

Have you ever seen that before?

NORTON: No!

God, no.

GATES: And a window into the hidden past.

(gasps).

ROBERTS: Oh.

It's so good.

Oh.

That's so good.

(laughs).

ROBERTS: Oh my gosh, I cannot believe this.

NORTON: It just makes you realize what a, what a small, you know, piece of the whole human story you are.

ROBERTS: Is my, is my head on straight still?

Am I facing you?

(laughter) GATES: My guests have spent decades in the limelight, followed by cameras at every turn.

In this episode, we're going to look at something those cameras have missed introducing Julia and Edward to the ancestors who fill the distant branches of their family trees, forever altering how they see themselves.

(theme music playing).

♪ ♪ MAN: Julia, Julia, Julia!

Julia!

GATES: Julia Roberts needs no introduction.

The beloved star with the iconic smile has been a Hollywood powerhouse for more than three decades.

Indeed, it's almost impossible to imagine Hollywood without her.

But Julia's success was by no means pre-ordained.

She grew up in Smyrna, Georgia, a suburb of Atlanta.

Her parents met when they were both aspiring actors.

And though their marriage didn't last, their ambitions did, and were passed down to their children.

After high school, Julia set off for New York, with her sights on the stage.

The transition proved challenging, but her mother pushed her on.

ROBERTS: My mom felt that moving was probably a good idea, and I know that once I moved and got a taste of the big city life and was terrified and asked her if I could come home, she said no.

(laughter).

GATES: You really wanted to go back?

ROBERTS: Yes.

I was really afraid all the time.

You know, I was 17 years old and I came from such a small place.

It was really intimidating.

I mean, I think about it now, if my daughter, who will be 17 next month.

If she moved to New York City?

GATES: No way.

ROBERTS: I, I'd be in the apartment next door, you know?

I mean, that's my mother putting her love for me, ahead of her wanting me close, because I'm sure she, in the same way that I want to keep my daughter close, it's the right love that says, no, you need to stay where you are and do the work.

GATES: Julia would, of course, remain in New York.

But success did not come immediately.

She started out selling sneakers in a shoe store, and spent years just trying to break into the business.

Along the way, she learned a lesson that would serve her well, both on and off camera.

ROBERTS: My husband and I the other day, we were in the kitchen and we, uh, I had the TV on in the, in the kitchen, and I was doing dishes, and he came in and, and, and the news was over and a soap opera came on, and it happened to be the soap opera that I used to watch as a young girl with my mom and my sister, and I haven't seen it in so long, and some of the same people are on it.

GATES: Huh.

ROBERTS: And I said to my husband, you know, there was a time when I moved to New York that I auditioned for a few soap operas and I auditioned for commercials, I auditioned for all kinds of TV shows, I didn't get any of them.

Thank goodness.

I would have not found this if I had found a great soap opera job when I was 18 years old.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

You'd still be on Search for Tomorrow or... ROBERTS: I would be.

GATES: Yeah.

ROBERTS: And so, it's amazing the things that don't work out for you.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ROBERTS: Um, because yeah, there was a time, what kind of job was I looking for?

One that would pay me.

GATES: Right.

ROBERTS: So I could pay my rent.

GATES: Right.

ROBERTS: And I'm really glad that the ones that I did find, that found me in the beginning of my career, were ones that still aligned with my sense as an actor in some way.

GATES: And, and, and fostered growth.

ROBERTS: Yes.

MAN: Excuse me, um, do you play?

GATES: For Julia, "Growth," is an especially meaningful term.

ROBERTS: Sure.

(doorbell rings) What is that?

GATES: Over the years, she's moved effortlessly from blockbuster romantic comedies to darker and more dramatic films, ROBERTS: First of all, since the demur we have more than 400 plaintiffs in.

Let's be honest, we all know there more out there.

GATES: Expanding her range, and at each step solidifying her fame.

And now looking back on all she's accomplished, Julia returns to her parents, and their struggles, with an immense sense of gratitude.

ROBERTS: It was always very, uh, much a part of my, my everyday thoughts of success, knowing that they didn't accomplish success the way that they wanted to, and I think that that was part of what dismantled their relationship, because I think my mom was always, that my dad was the love of her life.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ROBERTS: And so I think I always felt, um, very grateful in my own body, and then had this sort of extra dose of appreciation that came from knowing that it's not about being any better... GATES: Mm-hmm.

ROBERTS: That I certainly never thought that I'm a more talented artist than my parents, it was just time and place and opportunity.

GATES: My second guest is Edward Norton.

Like Julia, Edward's one of the most accomplished actors of his generation, blessed with an almost mercurial ability to blend intelligence with emotion.

(slaps) Since his breakout in the 1996 film, Primal Fear, Edward has moved between high-octane dramas.

(grunting) Indie comedies.

And Marvel movies.

(screaming) Earning three Academy Award nominations, and innumerable rave reviews.

But the man who's brought so much passion to so many roles found that passion in a surprisingly low-key place; the local arts school in his hometown, Columbia, Maryland.

NORTON: A babysitter of mine, um, uh, went to that school and my parents took me to see her in the, in a play and that was it.

I, I like, I wanted to be in that play.

I, I, you know, but, but I soon after signed up for classes and started taking, you know, I took tennis lessons and all that too, but I, but I was going to theatrical arts school, uh, um, for classes from the time I was five and I loved it.

GATES: Do you remember the name of the play?

NORTON: I do.

It was called, it was called If I Were a Princess and it was a musical of Cinderella basically.

GATES: Your father thought it was Babes in Toyland.

NORTON: No.

He's wrong.

It was, I wanted to be one of Cinderella's mice.

(laughter) GATES: Edward never got to be a mouse, but he soon became a member of the school's troupe and performed regularly throughout his childhood.

In the process, he discovered something essential about himself.

NORTON: I learned that I liked that tribe of people.

You know, I liked thespians.

I liked the personality types of people who were in that trade.

They were fun.

They were funny.

Um, they, you know, they, they, there was a bohemian sensibility to being around those people and they were, you know, this, this play acting for a living, um, as silly as it is in many ways, I don't know.

There was, it, it seemed like the minstrel life to me in a way that, um, was, was seductive.

It was like this is was not a nine to, this is not working in the straight world.

You know what I mean, and it was like this secret club.

And I loved all of it.

I loved all the, um, I loved all the lure, the phraseology of the theater, the superstitions of not saying the Scottish plays name and don't whistle in a theater.

And where does that come from?

I, I, I, I thought the whole allure of the theater was very deep.

GATES: This, "Allure," would pull Edward from Maryland to Broadway and, ultimately, to Hollywood in a dizzyingly short time.

He was working with legendary playwright, Edward Albey, before his 25th birthday.

And was just 27 when he earned his first Oscar nomination.

But those same years were also marked by a terrible loss; his mother's death from cancer.

The tragedy transformed Edward, giving him a sense of perspective that he carries with him to this day.

NORTON: You know my mother passed away literally like two weeks before the Oscars that time.

You know, to say it has an equalizing effect is an understatement.

It, it, it almost, you know, numbed me to the, to the, it almost felt like in the, in the Peanuts cartoon where everything is going whun, whun, whun, whun.

GATES: Yes.

Right.

NORTON: You know?

A lot of that hoopla was happening over here while these kind of profound things were happening over here.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

NORTON: And so, it's surreal and, and devastating but then, too, you have this surreal experience that life is continuing.

Your life is continuing.

You're doing the things they wanted you to do and, you find that over time, through the grief, you find the relationship hasn't ended, it continues.

GATES: Uh-huh, right.

NORTON: You're still talking to that person.

You're still reaching out to them.

You're still not just thinking what would they do, but you're kind of like communing with them and hearing their advice, or you know, sensing their pleasure at the thing that's happening that you're sad that they're missing.

And it's not, you know, it's not, it's not a, um, it's not a total mitigation of your grief but it's a weird, it's strange how you discover that, that your sort of, you're not just carrying the torch.

You're kind of still in this conversation with them.

GATES: Both Edward and Julia clearly bear the imprint of their parents.

Now, each was about to discover how they'd been marked by their ancestors, in ways more obscure, but no less profound.

I started with Julia.

She was raised in Georgia, knowing that her mother's family was from Minnesota.

Beyond that, she'd heard stories about roots in Sweden, but had no idea if they were true.

We set off to find out.

In the 1940 census for Minnesota, we saw Julia's mother, Betty Lou Bredemus, living with her parents, as well as a 56-year-old widow named Lornore Bredemus.

Lornore's birth name was Elin.

She's Julia's great-grandmother.

And a tangible tie to her deeper origins.

ROBERTS: "Place of birth, Sweden."

GATES: Sweden.

Elin was born on April 30, 1884.

ROBERTS: Wow.

GATES: In Sweden.

ROBERTS: Wow.

GATES: Did you know that?

ROBERTS: Well, I mean, I thought there was Swedish, and now we have a confirmation.

Not that I wasn't believing my mom, but you just never know.

GATES: What's it like to see that in black and white?

That confirmed?

ROBERTS: It's pretty cool.

It's, uh, I can't wait for someone to ask me where I'm from now.

(laughs).

ROBERTS: Georgia no more.

(laughs).

GATES: This census was the beginning of a much larger journey.

In the province of Värmland, in west-central Sweden, we found Elin's baptismal record, which not only lists the names of her parents, Julia's great-great-grandparents, but also provides some telling details about their lives.

ROBERTS: "Name, Elin Maria.

Birth, April 30.

Christening, May 18.

Johan Jansson and Emma Kristiani Karlsdotter.

Married for six months."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

And Karlsdotter.

ROBERTS: Wait.

They were only married for six months?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

Yeah.

You did the math.

ROBERTS: Wow.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ROBERTS: People.

GATES: What's it like to see that?

ROBERTS: It's just so dear just to think of her having a christening, just to picture her as a baby.

GATES: And that's the church where she was baptized.

ROBERTS: And.

Oh.

Really?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ROBERTS: The church is still there.

GATES: That church is still there and you can see it.

ROBERTS: That's incredible.

GATES: This church evokes what many of us imagine when we picture Sweden; an idyllic place, where people are comfortable, secure, and live peacefully.

But that's not the place that Julia's ancestors inhabited.

Elin's parents, Julia's second great-grandparents, were Johan and Emma Jansson.

Her baptismal record refers to them as being, "Statares," meaning that they were itinerant farmhands, landless laborers who traveled from one estate to another doing seasonal work, living under a system that seems to have been designed to keep them impoverished.

ROBERTS: Look at their clothes.

Wow.

GATES: Statares had to be married, that was a rule, so both Johan and Emma would have worked together on the estate.

They likely worked seven days a week, including every holiday.

ROBERTS: I mean, some of these little girls, look at that boy.

He's serious.

GATES: Want to guess how much your ancestors would have been paid for all that hard work?

ROBERTS: Oh, I can't imagine.

GATES: Almost nothing.

ROBERTS: Wow.

GATES: In exchange for all that work, your ancestors would have been given meager housing, food, enough to subsist on, and very little money.

ROBERTS: Wow.

GATES: They had a hard life.

ROBERTS: It looks hard.

Maybe that's why nobody ever talked about it.

GATES: Statares were essentially their own class within Swedish society, existing at the very bottom of the social ladder.

Typically they lived in barrack-style dorms where multiple families would be housed together.

Rooms were damp and crowded, rife with rats and other vermin, as well as tuberculosis and dysentery.

Children like Elin were poorly educated, if they were educated at all.

ROBERTS: It sounds horrible.

And to have a baby in a place that has rats and cockroaches and rampant tuberculosis.

GATES: Mm, and to be all crowded in with people.

ROBERTS: Yeah.

GATES: No privacy.

No sanitation.

ROBERTS: Oh.

Wow, and how they obviously prevailed.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ROBERTS: I mean, I'm sitting here.

GATES: Right.

ROBERTS: They, they kept going.

GATES: Well, let's see what they did about this.

Could you please turn the page?

ROBERTS: Yeah.

Somebody had to get on a boat or an oxcart at some point, right?

GATES: Could you please turn the page?

ROBERTS: Okay.

GATES: You got it right.

ROBERTS: There's a boat.

GATES: There's a boat.

This is a list of passengers leaving the port of Göteborg, Sweden, on April 1, 1887, nearly three years after your great-grandmother's birth.

Would you please read who was on that ship?

ROBERTS: Okay.

"Johan Jansson, 27."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ROBERTS: "Birthplace, By..." GATES: Mm-hmm.

ROBERTS: "In Värmland."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ROBERTS: Destination, Minnesota.

GATES: Yep.

ROBERTS: "Emma, 28.

Birthplace, By in Värmland."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ROBERTS: "Elin, two years, 11 months.

Birthplace, By in Värmland."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ROBERTS: "Gustaf."

(laughs).

ROBERTS: Welcome, Gustaf.

"11 months.

Birthplace, By in Värmland."

GATES: You're looking at the record that records the moment your ancestors left Sweden for the United States of America.

ROBERTS: Amazing.

I mean, it just makes me think that they were very brave.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ROBERTS: To go off with two little children.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ROBERTS: To a whole other land, a whole other language.

It's very brave.

GATES: Mm.

They rolled the dice.

ROBERTS: Yeah.

I mean to get off this boat, and you're standing on a dock.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ROBERTS: And where do you go?

GATES: Yeah.

ROBERTS: How do you know where to go?

GATES: Right.

ROBERTS: You can't even read a sign.

Oh my gosh.

GATES: Julia's ancestor were fortunate in one regard; they were not alone.

During the 1880s, over 300,000 of their fellow Swedes migrated to the United States.

Many settling in the Midwest, drawn by economic opportunities not available in their homeland.

So Johan and Emma became part of a community of immigrants and in this supportive environment, they found a way to thrive.

ROBERTS: "John Johnson, head of household, 46, naturalized, plumber."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ROBERTS: Emma, wife, 41, wait.

She got younger?

GATES: Yeah.

She got younger.

(laughter) ROBERTS: Well done, Emma.

August, son, 15.

George, son, 13.

Freda, daughter, ten.

Charles, son, eight.

Albert, son, six.

Okay.

Give them some privacy.

GATES: Yeah.

ROBERTS: Clarence, son, four, and Edwin W, son, two.

GATES: Yeah.

They worked on, like clockwork.

ROBERTS: Yeah.

Once they had a door to close.

Wow.

GATES: There are your ancestors, Johan and Emma in Minneapolis with their eight children.

ROBERTS: One, two, three, four, five, six boys.

GATES: Mm.

ROBERTS: Wow.

GATES: And what's it like to see this, to think about how far they'd come in just 13 years?

If they'd stayed in Sweden they'd almost certainly all still be landless itinerant farmhands.

ROBERTS: Yeah, and maybe perished in those conditions.

GATES: Remember, tuberculosis was rampant.

ROBERTS: Yeah.

I mean, to see this, like, big, of course in my dreamy mind, happy family, and for him to be a plumber, which is a very good job to have.

GATES: Oh, indeed.

ROBERTS: That they were clever, that they had a plan, and it seems like they really fully executed it.

GATES: We had one more detail to share regarding this family.

Returning to Sweden, we found a wealth of church records, allowing us to trace back to Julia's sixth great-grandparents, who were born in small towns in Värmland almost 300 years ago.

ROBERTS: "Jonas Labäck."

Born in 1755.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

In Stenstad.

ROBERTS: And Maria Johansdotter, born in 1756.

GATES: In Färnebo.

ROBERTS: That's a cute name.

GATES: You are back to the year 1755 and 1756 on your mother's side of your family tree.

ROBERTS: I'm going to call that heavy Swedish.

GATES: That's heavy Swedish.

This is before the United States became the United States.

ROBERTS: Wow.

GATES: America was still a colony of Britain.

The revolution breaks out in 1775.

This is 20 years before the Battle of Lexington and Concord.

ROBERTS: Wow.

GATES: And we have gone back that far in your family tree.

ROBERTS: This is amazing.

GATES: Are you feeling more Swedish than you were two hours ago when you walked into this building?

ROBERTS: I, I'm going to be insufferably Swedish when I walk out of here.

You have no idea.

I know one Swedish word, and it's going to be on repeat.

GATES: Ja.

ROBERTS: Hallå.

That's my only Swedish word.

GATES: What's that mean?

ROBERTS: Hello.

GATES: Oh.

(laughter).

GATES: Like Julia, Edward Norton was about to travel deep into his family's past.

But before we could begin that journey, we had to navigate an unusual obstacle; Edward's own knowledge of the subject.

Edward is a passionate student of history, and especially the history of his own family.

In fact, he came to me knowing more details about his roots than any guest I can recall.

GATES: How do you know so much about your family tree?

NORTON: Well, I was, I was fascinated by it.

I'm fascinated by, um, the idea of roots, the idea of, of what drives people to leave one place and go to another, um, is, is fascinating to me.

GATES: Usually something bad.

NORTON: Often.

Yeah.

GATES: Rich people don't migrate.

(laughter).

NORTON: Um, but I think, you know, I, I was, I was lucky.

I had grandparents, for instance, who, I knew my, my grandfather was Ed Norton and his grandfather was named Seneca Hughes Norton and we knew not only that he had gone to West Point during the Civil War, graduated and was part of, um, I think, Phil Sheridan's second calvary in Montana, in the Montana territories in the 1870s but not just that, we have his journals.

GATES: Yeah.

NORTON: We, we have two leather bound journals that, that he wrote in and when he ran out of space, he turned it 90 degrees and wrote across the lines, and my grandparents had sat there with a magnifying glass and picked it out and transcribed it, so I had that kind of thing.

GATES: Wow.

You were very lucky.

Very.

NORTON: Very lucky.

Very lucky in that sense.

Yeah.

GATES: Given the extent of Edward's knowledge, I was worried that we might not be able to uncover anything new about his family tree.

Fortunately, our researchers didn't disappoint.

Discovering a slew of surprising stories.

The first began on Edward's father's line, with his great-great-grandfather, a man named Frank Baals.

Frank died in Ashland, Kentucky in 1905.

According to his obituary, he worked as a yardmaster for an Indiana railroad company in the 1890s.

A time of great turmoil in America's labor movement.

Indeed, Edward was on the job during the notorious pullman strike, which ended in open battles between striking workers and the United States military.

Any family stories about that?

NORTON: No.

I've heard that name, not even Frank, but the, the name Baals I knew was within my, um, my grandfather's, you know, paternal lines, but I literally never even heard a story.

GATES: Could you please turn the page.

NORTON: Yeah.

GATES: It turns out there's more to his death than that obituary let on.

NORTON: Wow.

"Frank Baals was murdered."

"The fact that the late Frank Baals was probably murdered became known here yesterday for the first time when his alleged slayer, Rat Haney, was placed on trial in Catlettsburg, Kentucky.

No motive for the murder of Mr. Baals has yet been discovered.

He had money on his person on the night he met his death, but it was not touched.

His injuries were all about the head and were evidently inflicted by a club or other instrument.

A neighbor saw Mr. Baals on the night of the murder sitting in front of the barber shop.

He saw a man come along, strike Mr... Strike Baals over the head.

Mrs. Baals heard her husband call and running out upon the porch saw him hanging to a post, blood streaming from his wounds."

That is amazing.

I mean, what a story, uh, but certainly, I've never heard that.

Never, never, ever heard of anything like that.

I wonder if it was a disgruntled railroad worker who did.

GATES: Well, we're gonna find, we're gonna find out.

(laughs).

GATES: As a yardmaster, Frank was management, and when the strike came, it seems he stayed loyal to his company, working to keep the railroads running.

Which most certainly, would not have endeared him to the striking members of his community.

But Frank's unfortunate death may have arisen from a cause far simpler; it seems that Frank had a pension for arguing.

NORTON: "Those who were acquainted with Mr. Baals will remember that he was a very plainspoken man letting the result be what it would."

(laughs).

That sounds like someone who speaks uncomfortable truths.

"Yet he seemed unable to control himself sufficiently to avoid danger.

A few days before his death, he had been engaged in a political conversation with a number of men and is supposed to have expressed himself too freely upon the subject causing an ill feeling by some of the party."

(laughter).

GATES: According to this article, Frank was killed over politics.

What's it like to read that?

NORTON: Uh, I mean, amusing.

Not for Frank, but, um.

GATES: Well, we looked into Thomas Haney, the Rat.

NORTON: Right.

GATES: Um.

Rat Haney as he was called, and we discovered that he was a bartender in Ashland.

Perhaps Frank said something inflammatory in Haney's bar.

We can't say for certain.

Whatever it was about, it got heated enough for Thomas Haney to bludgeon your great-great grandfather in the head.

That amazing?

NORTON: Amazing.

GATES: And, and that story was not passed on.

I mean, for your family, which is extraordinarily prone to sharing stories, there's one that was filtered out, yeah.

NORTON: Its wild.

These are consequential...

These are consequential things.

GATES: Following a different branch of Edward's father's family, we soon came to another story that had not been, "Passed down."

Edward's third great-grandfather, a man who shares his name, became a wealthy iron manufacturer during the 19th century.

But sadly his childhood sounds like something out of a Dickens novel.

NORTON: "Norton began life at the bottom rung of the ladder starting as a nail feeder in Phoenixville, PA, then advancing as a nailer in, at Pittsburgh and later with E.W.

Stevens founding the first nail mill in the city."

GATES: Have you ever heard of a nail feeder before?

NORTON: No.

GATES: Okay.

They worked in iron mills placing worn nails or other scrap iron into a machine or into an open fire, so that it could be melted down and reused.

It was an essential part of the iron industry at the time, and it was dirty and dangerous and extraordinarily uncomfortable work.

There were explosions and fires in these mills all the time, and it was also frequently work done by children.

NORTON: Hmm.

GATES: Edward likely started in the mill as a teenager and almost certainly had no formal education.

Can you imagine?

NORTON: No.

But I think it's very hard for us today to conceptualize the violent danger of a child working in a blast furnace.

You know what I mean?

I mean, it's like... GATES: Picking up nails.

NORTON: We would no more let our children be anywhere near that environment.

You know what I mean?

It's, it's nuts to think about.

GATES: Yeah.

Yeah.

NORTON: It's, um... GATES: It should have been illegal.

NORTON: Absolutely.

GATES: Edward's ancestor never forgot his working-class roots.

Even as he built up his business, he remained a staunch supporter of what we would now call progressive causes.

What's more, when the Civil War came to Virginia where he was living, Edward sided with the Union, going so far as to offer his services as a United States Marshall in the fight against slavery.

NORTON: That's interesting.

You know, you want to try to prep yourself for having the nerve to do the same thing should a thing like that come along and it's, it's, it's cool to, it's cool to, you know, see small and big examples of it in, in the, in the kind of the quotidian details of what people went through during this totally intense time.

GATES: Yeah.

As a Marshall, Edward's ancestor followed his own conscience, refusing to help capture escaped slaves and, in July of 1862, he penned a remarkable letter to none other than Abraham Lincoln himself, urging the president to allow African American men to fight in the Union Army.

NORTON: "Dear Sir!"

With an exclamation point... GATES: I like that.

NORTON: "Excuse me for intruding this letter upon you.

If I did not love you and my country's noble government more than wife and children, I should not presume to write you.

I experienced a great joy at learning that you contemplate adopting, announcing the policy of using negro slaves of rebels for the purpose of assisting to suppress this accursed rebellion and for such service to free them and their families.

Such a proclamation will infuse new life and vigor in the hearts of all truly loyal men who are discouraged that hitherto they have not been permitted to use an instrument so potent for the nation's welfare."

GATES: What do you think of that?

Have you ever seen that before?

NORTON: No.

God, no.

GATES: It's amazing.

NORTON: Yeah.

That is uh, that is really interesting.

GATES: Yeah.

He's saying you should arm Black men.

NORTON: That's amazing.

GATES: Now, Lincoln would eventually do this but on the day he received that letter, he had not made this decision.

NORTON: And that's in 1862.

GATES: Yes.

For a White man, your third great grandfather was very much ahead of his time.

It was a radical thing to arm Black men to kill White men.

NORTON: "Using slaves of rebels for the purpose of assisting to suppress this accursed rebellion."

I mean, that's, that's pretty unequivocal.

GATES: What's it like to read the words of your ancestor writing to President Abraham Lincoln?

NORTON: He's eloquent.

It's the inverse of like pride in a child, right?

You want your, more than anything you want your children to do the right thing probably, right, but it's neat, in some weird way, you, you hope your ancestors did the right thing somewhere and you can take some kind of inspiration or pride in it.

GATES: Well.

NORTON: It's incredible.

GATES: I want to show you one more thing... NORTON: Okay.

GATES: About your namesake.

Would you please be kind enough to turn the page?

NORTON: Oh.

Look at that.

Is that a portrait of him?

Oh, wow.

Amazing.

GATES: Yes.

You've never seen him before?

NORTON: Never.

Uh-huh.

GATES: That's Edward.

NORTON: That is amazing.

He, he looks like my, my dad's dad, um, but he looks sort of like, it's really funny.

He looks sort of like Walter Houston, you know, the great character actor in Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

GATES: I love Walter Huston... NOROTN: He doesn't look that distinguished.

He looks, he looks like he's sort of from the frontier.

I like that.

He's got a little bit of a, of a miner 49er kind of look to him.

That's great.

What a mustache.

GATES: We had one more surprise for Edward.

He'd grown up hearing that his father's roots traced deep into colonial Virginia's past, and that he was, in fact, a direct descendant of Pocahontas, the Powhatan woman who married the Virginia settler John Rolfe, in the colony's earliest days.

Edward was convinced that Pocahontas's place on his family tree was a family legend, a product of generations of wishful thinking.

But it turns out Edward was wrong.

Pocahontas is indeed your 12th great grandma.

NORTON: Oh, my God.

(laughs) GATES: I understand that was family lore.

Well, it is absolutely true.

NORTON: And how could you possibly determine that?

GATES: Through the paper trail.

NORTON: It would have been documented... GATES: Oh, yeah.

NORTON: They would have a paper trail of their children?

GATES: Of course, John Rolfe and Pocahontas got married on April 5, 1614.

Shakespeare dies in 1616, just to put this in perspective.

NORTON: Married in North America or, he had taken her back to... GATES: No they, in Jamestown, Virginia, we think.

Pocahontas died sometime in March 1617 in Gravesend, England and John Rolfe died around March 1622... NORTON: So they were married in 1614.

GATES: 1614 when Shakespeare was still alive.

But you have a direct paper trail, no doubt about it, connection to your 12th great-grandmother and great-grandfather John Rolfe and Pocahontas.

NORTON: This is about as far back as you can go.

GATES: It's as far back as you can go.

NORTON: And that's it, unless you're a Viking.

GATES: Yeah, that's right.

NORTON: It just makes you realize what a, what a, what a small, you know, piece of the whole human story you are.

GATES: We'd already traced Julia Roberts' maternal roots back to Sweden, introducing her to a host of ancestors whose names had been lost when her family moved to America.

Now, turning to the paternal side of Julia's family tree, we found ourselves in south-west Georgia, exploring a name that had been lost for a very different reason.

The story begins with Julia's great-grandfather, John Roberts, who grew up on a farm with his mother, a woman named Rhoda Suttle.

Ever hear that name?

ROBERTS: No.

GATES: Well, I want to tell you about her.

Would you please turn the page?

ROBERTS: Suttle is not anything anyone has ever called anyone in my family, by the way.

GATES: This is the 1880 census for Douglas County, Georgia.

ROBERTS: Wow.

GATES: There's your great-grandfather John, you see him, right?

As a child.

ROBERTS: Whose two years old here?

GATES: He is two years old.

Uh-huh.

Living with his mother, your great-great grandmother Rhoda Suttle Roberts.

Right?

ROBERTS: Right.

GATES: And three brothers.

You notice anyone missing?

ROBERTS: A dad?

GATES: A dad, the dad is missing.

John's father, Rhoda's husband isn't there.

Have you ever heard anything about him?

ROBERTS: No.

GATES: Digging into Georgia's county archives, we discovered that sometime in the 1850s, Rhoda married a man named Willis Roberts.

Julia carries Willis' last name, but Willis passed away in 1864, over a decade before Rhoda gave birth to Julia's great-grandfather, John, leading to an inescapable conclusion.

Julia, Willis Roberts could not possibly be your great-great grandfather.

He was dead.

ROBERTS: But, oh.

Wait, but am I not a Roberts?

GATES: Well, let's see what we found.

We scoured Douglas County looking for any record that named John's father and we found absolutely nothing.

ROBERTS: Wow.

GATES: Douglas County didn't issue birth certificates in 1878 and marriage certificates didn't name parents' names at the time.

Fortunately, we had another tool, and that was DNA.

ROBERTS: Wow.

GATES: Julia and one of her father's first cousins, a fellow descendant of John Roberts, both agreed to take DNA tests.

We then compared their results to people in publicly-available databases, searching for matches, and looking to see how those matches might be connected, hoping to identify John's father through the DNA of his descendants.

In the end, we found a cluster of matches that tie Julia and her cousin to one man.

ROBERTS: "Henry McDonald Mitchell Jr." GATES: You just read the name of your biological great-great grandfather.

ROBERTS: So, we're Mitchells?

GATES: You're Julia Mitchell.

You are not a Roberts biologically.

ROBERTS: Wow.

That is crazy.

I, I bet nobody knew.

GATES: Well, everybody near that farm knew because her husband wasn't there and she was still having babies.

ROBERTS: Wow.

Is my, is my head on straight still?

Am I facing you?

GATES: There's no way to tell if Rhoda ever told John the identity of his father.

But we found a reason to think that she might have kept it a secret.

In the 1880 census, recorded when John was two, his biological father Henry Mitchell is living with his wife, a woman named Sarah, along with their six children.

And he lived just a few miles from Rhoda.

ROBERTS: A few short miles, it would seem.

(laughs) GATES: Get this, according to the same census, Henry's widowed mother, Elizabeth Mitchell, lived just four households from Rhoda.

ROBERTS: Wow.

GATES: What's it like to see that?

Henry was married but his mother lived close to your great-great-grandmother.

So, he would go see his mother like a good boy.

ROBERTS: Gosh.

And Sarah was probably saying, "Aww, you're going to go see your mom?

That's so sweet."

Wow.

GATES: What are you feeling right now, Mrs. Mitchell, I mean, Mrs. Roberts?

(laughter) ROBERTS: I mean, it's, you know, on the one hand, truly, my mind is blown.

Um, and it is fascinating, and on the other hand, there's, you know, part of me that when I'm calmer, you know, can still wrap my arms around the idea that, you know, that my family is my family.

GATES: Of course.

ROBERTS: And I do prefer the name Roberts.

(laughter).

GATES: That is your name.

ROBERTS: Um, yeah.

It's, this was a very unexpected turn, Doctor.

GATES: Regrettably, it seems that Henry Mitchell was a mysterious man in more ways than one.

Sometime after 1880, he moved from Georgia to Arkansas, where he essentially disappeared from the paper trail.

But Henry's roots, Julia's newfound Mitchell ancestry, were another matter.

They can be traced deep into the past, all the way back to colonial Virginia in the 1700s.

One side of your family immigrates in 1887, the other side has been here since before America was America.

ROBERTS: Wow.

GATES: You have a deep purchase on the United States of America.

ROBERTS: I like those words.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ROBERTS: I mean, it's just so nice to know something.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ROBERTS: I mean, to know, it's not like I knew, I thought I knew everything and you're telling me I knew everything.

I didn't know anything.

GATES: Right.

ROBERTS: And even though what you're telling me is a wild ride, it's, knowledge is power and connection.

GATES: I had one more story for Julia, a story that would add another layer of complexity to her new family tree.

Moving back on her father's mother's line, we came to Julia's fourth great-grandfather, a man named Edward Townsend.

We found Edward in the 1850 census living in Georgia, owning a farm of more than 2,000 acres.

But that wasn't all he owned.

ROBERTS: "Slaves, one female, 33 years old, one female, 20 years old, one female, 17 years old, one female, 13 years old, one female, 11 years old, one female, eight years old, one male, six years old."

GATES: Now, you're a Southerner.

Did you ever consider the possibility that your ancestor or any of your ancestors could have owned enslaved people?

ROBERTS: Yes, yeah, you have to figure if you are from the South, you're on one side of it or the other.

GATES: Right.

And some of the people enslaved were just children.

There are three teenagers, an eight-year-old boy and a six-year-old boy.

ROBERTS: And they must be the children of the older women.

GATES: You got it.

ROBERTS: Mm-hmm.

GATES: And we don't know who their fathers were or who their father was.

ROBERTS: That's sad.

GATES: Yeah.

ROBERTS: I mean, it just seems very typical of that time, unfortunately, and you know, something to know and to, um, uh, understand and accept, and you know, not shy away from.

You can't turn your back on history even when you become a part of it in a way that doesn't align with your personal compass.

GATES: Turning from Julia back to Edward Norton, we discovered that he, too, had slave-owners in his family tree.

The 1850 census for North Carolina revealed that his third great-grandfather, a man named John Winstead, held seven human beings in bondage.

NORTON: So, this is a 55-year-old man, a 37-year-old woman and, and five girls ten, nine, eight, six and four.

GATES: That's right and he owned them.

What's it like to see that?

NORTON: Like, the short answer is these things are uncomfortable.

Like, and you should be uncomfortable with them.

Like everybody should be uncomfortable with it.

It's, whether it, you know, it doesn't, it doesn't know...

It's not a judgment on, on you in your own life but it's a judgment on the, it's a judgment on the history of this country and it, and it, and it needs to be acknowledged first and foremost, and then, it needs to be contended with.

GATES: Absolutely.

NORTON: I mean when you go away from census counts and, and you personalize things, you're talking about possibly a husband and wife with five girls and the, and these girls are slaves, you know, born into slavery.

It's just like, you know.

GATES: And born into slavery and in slavery and in perpetuity.

NORTON: Yeah.

It's, you know, it's again, when you read, "Slave age eight," you want to die.

GATES: John Winstead embodies one of the ugliest chapters in American history.

But as we pressed on, we soon saw another, far nobler side of that history emerge on this same branch of Edward's family tree.

The story begins with Edward's sixth great-grandfather, Moses Walker, a man who was willing to risk his life for our country at its inception.

NORTON: "Moses Walker, private.

McRree's Company.

Sixth North Carolina Regiment.

Date of enlistment, October 1777.

Omitted February 1778."

GATES: So, you know what this means?

NORTON: Uh, served in the Continental Army?

GATES: Yeah, you, you descend from a patriot.

Moses Walker served in the Continental Army during the American Revolution.

We believe that Moses was born around 1730 either in Virginia or North Carolina, and he would have been in his 40s when he enlisted.

NORTON: That's interesting.

GATES: And that is his company's muster roll.

What's it like to see that from 1777?

NORTON: Unbelievable.

I mean, I got to be honest, like, one of the things that amazes me is that they were making these kinds of records like in that kind of a tumultuous time.

GATES: A, that they were making the record and B, that the record is still here.

NORTON: Yeah.

I mean, a, a muster roll from 1777, like as they're scrambling to get people enlisted.

It's wild.

GATES: Do you feel any kinship here, Edward?

NORTON: Yeah.

I mean, I think, I think, uh, the, again, it's just, um, it, there's a certain, uh... You can't not get a warm feeling at any, whether it's your ancestor or not like displaying a certain kind of a courage on and conviction on behalf of someone else.

GATES: Moses volunteered in October of 1777 and served during a very important moment in the war.

His regiment fought under George Washington at the battle of Germantown, a patriot defeat on the outskirts of Philadelphia, and then spent that winter with the colonial forces as they, famously, regrouped in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania.

And we believe that he was there.

Did you ever think you might have an ancestor who was in George Washington's army?

NORTON: No.

But I had never heard anything about this.

And also, I noticed one of my reactions to that is you have this tendency partly because of the sort of the, the, the negative connotations of the Southern states in the Civil War and the Confederacy and all these things, you, you tend to ascribe the Revolutionary War to the Northeast, GATES: Oh, right.

That's true.

NORTON: And you forget, this is like a North Carolina regiment in the Revolutionary War and that sort of blows my mind.

GATES: There were 13 colonies.

NORTON: I know and you, but you, you, you forget that they all came together and sent their reps, and when they went at this, people went all the way from North Carolina in 1777 to go fight with George Washington?

I mean, that is unbelievable.

GATES: Right.

It is unbelievable.

NORTON: Think about the journey just to get up there.

I'm serious.

Like, 1777 to go from North Carolina to Philadelphia by horse.

GATES: Yeah.

Or walking.

NORTON: Yeah.

I mean, I mean, that is, that's just unreal.

GATES: Moving back three more generations, we encountered a man who did something even more, "Unreal."

Edward's ninth-great-grandfather, Daniel Winstead, was born in Chichester, England around 1650.

We found him in the archives of colonial Virginia in 1671, paying 1,000 pounds of tobacco for 50 acres of land.

Meaning that as a young man, Daniel left his home behind forever and crossed the Atlantic.

So, this is your original, immigrant ancestor on that branch of your family tree.

NORTON: Wow.

And came to Virginia, and then, bout some, sold some tobacco for some land.

GATES: You got it.

NORTON: Fascinating.

What made that guy leave then, you know, I mean... GATES: Yeah, well he wasn't... NORTON: For the absolute wilderness of North America?

GATES: Well, he wasn't in line to inherit Downton Abbey.

NORTON: That, well that's for sure.

They probably, the probably asked him to clean up Stonehenge one too many times and he said, "I'm out of here."

(laughter) GATES: Daniel Winstead is representative of multiple ancestors on Edward's tree.

All told, we found more than a dozen of his relatives who immigrated from England to America, but while Edward's roots are predominantly English, they are not exclusively so.

We were also able to trace him back to France, Germany, and Belgium.

And his DNA suggests he has significant Scottish ancestry as well.

Surveying it all, Edward was struck by a larger lesson.

NORTON: It's like wait a second.

Everybody was an immigrant.

Everybody went through the experience.

Everybody's ancestors came from somewhere.

They came from somewhere for some reason.

GATES: Everybody.

NORTON: And, and all you got to do is do this a few rows back and everybody's got the same story.

GATES: We're a nation of immigrants.

Everybody.

NORTON: And it's like why isn't that, why that doesn't bind us up in, in a, in a, you know, in a sense of pride.

GATES: Yeah and everybody came here fleeing something.

NORTON: Yeah, it's the energy of the country.

GATES: The paper trail had now run out for each of my guests.

ROBERTS: Wow.

(gasps).

Oh, look at everybody.

GATES: It was time to unfurl their full family trees.

These are all of the ancestors... NORTON: Wow!

GATES: That we uncovered on all lines of your family tree.

NORTON: Wow.

GATES: And then see what DNA could tell us about their deeper roots.

As it turns out, Julia and Edward were in for a shared surprise.

When we compared their DNA to that of everyone else who's ever been in the series, we found significant matches.

Evidence of a distant cousin for each of them.

Revealing a hidden relationship that neither had ever imagined possible.

All right.

Please turn the page.

(laughter) NORTON: Julia Roberts, everyone.

ROBERTS: What?

GATES: Your DNA cousin is Edward Norton.

Have you ever worked with Ed?

ROBERTS: No.

I mean, I've met him but I've never worked with him.

GATES: You and Ed share a long identical stretch of DNA on your ninth chromosomes.

This means that you two inherited that shared DNA from a distant ancestor somewhere in the thicket of that family tree of yours.

ROBERTS: Wow.

NORTON: How come I didn't get the teeth and the smile?

(laughs) GATES: That's the end of our journey with Julia Roberts and Edward Norton.

Join me next time when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests on another episode of Finding Your Roots.

Edward Norton's Great-Great-Grandfather Was Murdered

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S9 Ep1 | 4m 3s | Edward Norton knew a lot about his family history, but was unaware of one shocking death. (4m 3s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S9 Ep1 | 33s | Edward Norton and Julia Roberts discover their hidden connections to American history. (33s)

Julia Roberts Learns of Swedish Ancestors' Humble Beginnings

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S9 Ep1 | 5m 50s | Julia Roberts learns about the harsh living conditions of her Swedish Ancestors. (5m 50s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by: