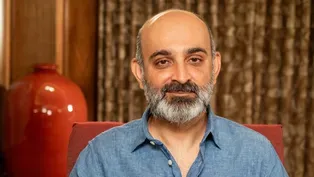

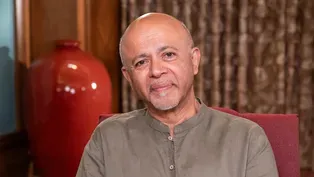

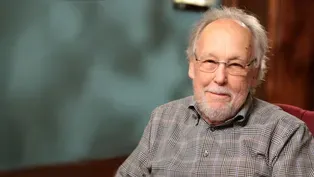

Public Historian Tom Ikeda

Season 2021 Episode 2 | 28m 47sVideo has Closed Captions

Tom Ikeda talks with Marcia Franklin about his nonprofit, Densho.

Tom Ikeda, who provided critical research for Daniel James Brown’s book “Facing the Mountain,” discusses his Seattle-based non-profit, Densho. It preserves the stories of Americans of Japanese descent during World War II. Ikeda’s parents and grandparents were imprisoned in the Minidoka camp in Idaho.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Dialogue is a local public television program presented by IdahoPTV

Major Funding by the Laura Moore Cunningham Foundation. Additional funding by the James and Barbara Cimino Foundation, the Friends of Idaho Public Television and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Public Historian Tom Ikeda

Season 2021 Episode 2 | 28m 47sVideo has Closed Captions

Tom Ikeda, who provided critical research for Daniel James Brown’s book “Facing the Mountain,” discusses his Seattle-based non-profit, Densho. It preserves the stories of Americans of Japanese descent during World War II. Ikeda’s parents and grandparents were imprisoned in the Minidoka camp in Idaho.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Dialogue

Dialogue is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Dialogue Podcast

Now you can listen to Dialogue wherever you are -- while you exercise, while you drive, or at home. Just search for “Dialogue with Marcia Franklin” on Apple Podcasts and other podcast platforms. And remember to subscribe, so that new shows download automatically!Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMore from This Collection

Video has Closed Captions

Marcia Franklin talks with historian Tiya Miles at the 2024 Sun Valley Writers’ Conference. (28m 47s)

Video has Closed Captions

Marcia Franklin talks with Rabbi Sharon Brous at the 2024 Sun Valley Writers’ Conference. (28m 47s)

Video has Closed Captions

Marcia Franklin talks with journalist Clarissa Ward at the 2024 Sun Valley Writers’ Conference. (28m 47s)

Video has Closed Captions

Marcia Franklin talks with Margaret Atwood at the 2024 Sun Valley Writers’ Conference. (28m 45s)

Video has Closed Captions

Marcia Franklin talks with novelist Mohsin Hamid about “The Last White Man.” (28m 46s)

Video has Closed Captions

Marcia Franklin talks with journalist Andrea Elliott about her book, “Invisible Child.” (28m 45s)

Video has Closed Captions

Marcia Franklin talks with author David Grann about “The Wager.” (28m 45s)

Video has Closed Captions

Marcia Franklin talks with Hernan Diaz about his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, “Trust.” (28m 46s)

Video has Closed Captions

Marcia Franklin talks with novelist Abraham Verghese about “The Covenant of Water.” (28m 46s)

Video has Closed Captions

Part Two of Marcia Franklin's conversation with Barry Lopez about his life and work. (28m 47s)

Video has Closed Captions

Part One of Marcia Franklin's conversation with Barry Lopez about his life and work. (28m 47s)

Video has Closed Captions

A conversation with author Brando Skyhorse about memoir, "Take This Man." (28m 46s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipPresentation of Dialogue on Idaho Public Television is made possible through the generous support of the Laura Moore Cunningham Foundation, committed to fulfilling the Moore and Bettis family legacy of building the great state of Idaho.

By the Friends of Idaho Public Television, and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

With additional funding from the James and Barbara Cimino Foundation.

Tom Ikeda, Founder, Densho: We realized that more than just documenting history, it was actually healing a community that was still suffering from post-traumatic stress syndrome.

Marcia franklin, Host: Coming up, I talk with Tom Ikeda, the founder of Densho, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the stories of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

That's "Conversations from the Sun Valley Writers' Conference," next.

Stay tuned.

[MUSIC] Franklin: Hello and welcome to Dialogue.

I'm Marcia Franklin.

When Tom Ikeda was growing up in Seattle, he knew his parents had experienced hardship when they were just children themselves.

Both had been incarcerated in the Minidoka relocation camp in Idaho during World War II.

Nearly 10,000 people of Japanese descent were forced to relocate to the Minidoka site between 1942 and 1945.

But his parents' stories of that time were locked away in their hearts and minds as they moved on with their lives.

Ikeda, a third generation Japanese-American, would only learn more about their experiences decades later.

As you will hear, after a series of meetings that changed his life, he became the founding director of Densho.

That's a Seattle-based nonprofit dedicated to preserving the stories of Japanese-Americans like his parents and grandparents who were imprisoned in the united states during World War II.

Densho, which means "pass on to future generations" in Japanese, has amassed a huge collection of interviews, photos and documents from that time.

And 25 years after starting the organization, Ikeda isn't slowing down.

He recently provided critical research for "Facing the Mountain," a new book by best-selling author Daniel James Brown.

It documents the heroism of the 442nd regimental combat team, a segregated Japanese-American unit that fought in World War II.

I spoke with Ikeda at the 2021 Sun Valley Writers' Conference about the book, and about the passion that continues to drive him.

Thanks for taking the time to be here with me.

I really appreciate it.

Ikeda: No, thank you, Marcia.

This is, it's always fun to be able to talk about the Japanese American experience.

Franklin: First of all, I want to congratulate you on your 25th anniversary, is that correct?

Of Densho.

Ikeda: It is.

Not that many people know about this, but yeah, back in 1996 is when we started Densho back in Seattle.

Franklin: And you'd been working for Microsoft.

Is that correct?

Ikeda: Yeah.

Prior to that, I, um, worked at Microsoft in the, it was called back then the multimedia publishing, um, department.

And we did, it was the old CD rom technology, for old-timers.

And, and my project was, you know, putting like encyclopedias on CD ROMs that had videos, images, and, you know, the things that you take for granted on the internet now, you know, back 20, oh, like 30 years ago, we had to do it on these discs.

Franklin: I think I remember that.

Ikeda: Yeah, Encarta.

Franklin: Encarta, yeah!

I remember that.

So what was the, you know, driving force in starting Densho?

I mean, you had a wonderful job and, what was propelling you?

Ikeda: Well, so I, I actually had left Microsoft to take a couple of years off.

And I was, um, I remember I was, I was in the kitchen one day --you know, my job was to really be the stay-at-home dad -- and got a call from, uh, an ex-Microsoft Vice-President, Scott Oki.

And he called me and said, "You know, there's this project that we, um, he heard about called the Shoah Project.

And this was a project that Steven Spielberg had started after "Schindler's List."

And, and this project was documenting the testimonies of Holocaust survivors.

And Scott said, "Let's go down and check them out, because, um, we should try to do something for the Japanese-American community."

So we went down there, got the grand tour, and it was, it was just amazing what they were doing.

They were, um, you know, video recording tens of thousands of survivors.

They were digitizing them.

Uh, they were putting them, um, on these workstations.

The one thing that I noticed though, coming from Microsoft, was that I felt that we could replicate everything on personal computer technology.

Back then, the Shoah project was using all mainframe technology.

So I think their budget was like 50 to 60 million dollars.

And, and we wouldn't have anything close to that.

But I said, "But Scott, I think with, with microcomputers, with personal computers and with the internet, we can pretty much do all these things for, for, you know, a fraction of the cost."

And so that was the genesis of Densho.

It was really kind of our technology background and coming to the community and knowing that these stories are really important.

So that, that's how we started.

Franklin: Well, let's pick up on that, that part.

What was it that you and Scott were so determined to do and to preserve, um, using that model of the Shoah Project?

Ikeda: Well, so Scott and I, um, both our parents were incarcerated during World War II.

So we knew the story.

And we also knew that the community had not really shared the, the, stories.

And so the question we kind of posed to each other is, "What would happen if Japanese-Americans shared the story of the World War II incarceration?"

We thought it would, it would impact our country.

We'd learn from it.

You know, we, we didn't anticipate some of the things that have happened the last few years.

But it's, it's been very useful I think, for the country.

We've, we've gone around, we've shared the story and people see a lot of similarities to what happened to Japanese-Americans during World War II to what is going on in our country today.

Franklin: How many interviews have you now taped for Densho?

Ikeda: Yeah, so we have about a thousand, of which I've, I've actually done 250 of these interviews.

So like you, you've done lots of interviews and, and in some ways they're my books.

I learn so much about history by just interviewing people.

Franklin: Were people reticent?

Ikeda: Yeah.

So here's, here's another story.

So 26 years ago, you know, 1996, I go to my dad and I said, "So dad, we're, we're going to do this project.

We're going to go into the community, interview people."

And he told me, "Don't, don't do it."

And I said, "Well, dad, I mean, so many people don't know the story.

Why not?"

And he said, "Well, you're going to bring up so many painful memories.

And most people aren't going to want to talk about this."

And in some ways he was right.

I mean, it was very painful, l and initially people were reluctant.

But I think the word got out, and there wasn't so much that we were collecting history.

When someone shares a painful story, and sometimes for the first time, it is such a release.

And we were finding that, especially in the early days, we were interviewing people who had never talked about what happened to them.

And this is oh, back then, so it's about 50 years after the fact.

And the emotions that would come out, um.

And the other thing we saw, though, was that when the interview was completed, it was really like a weight came off the shoulders.

And I remember getting phone calls from the children, or even the grandchildren of the people we interviewed.

And they're saying, "What, what happened to mom?

I mean, she's now sharing things she had never shared before."

And we realized that more than just documenting history, it was actually healing a community that was still suffering from post-traumatic stress syndrome.

Franklin: Did your father do an interview?

Ikeda: He did.

And today he's still alive, he's 94, and he's, uh, the biggest fan of what we're doing.

And we are so much closer, because by me doing this project, learning so much, you know, we have so many discussions, because he still is my closest advisor.

I mean, he knows, you know, the people, the, the, the events, because he lived through them.

And so whenever I, I'm struggling with a topic or, or even a person to interview, you know, he usually has really good advice.

Franklin: And your mother?

Ikeda: My mother is still alive.

Um, it's more painful.

She has not agreed to be interviewed.

Um, you know, about 10 years ago, so after I had been doing Densho for 15 years, uh, I was home, um, at the family house and she came out with a photo album and she said, you know, it was just the two of us.

And she said, "There's something that you should know about."

I said, "Oh, so what is it?"

And she pulled out, you know, kind of her personal photo album.

And it was her as a, as a kid.

And, uh, she and her younger brother went to Japan with, uh, her, her mother.

And, uh, so there were photos there.

And, and slowly we went through it.

And then she came across this photograph of her parents, you know, my grandparents, accepting this flag at the Minidoka, Idaho concentration camp.

And she says, "So this is something you have to, to know about."

And I had known that her older brother was killed in action.

But she told me, you know, this, this very, um, for her, very difficult story, even for me, where her older brother, who was at the University of Washington in the ROTC program.

Um, so when he was rounded up with the rest of the family, taken to Puyallup and then to Minidoka, Idaho.

Um, when Japanese-American men were able to volunteer for the army, you know, he was like first in line.

And when he took his physical, he failed, because he had a kidney ailment.

And so my grandmother gave him a herbal home remedy.

And he took it and then he went back and passed the physical.

And so he went to basic training, uh, became a Staff Sergeant, uh, as part of the 442nd.

And then was killed in Italy with a sniper bullet.

And when the, my grandparents, uh, heard about that, my mom was there when they got the news.

Um, my, my grandfather was, was so despondent.

I mean, you know, his oldest son, uh, you know, for him, you know, the pride and joy of the family.

And he was so angry, he lashed out at my grandmother and said, "You, you killed our son."

And for my mom, that, that was so traumatic to see that happen.

And when I asked my mom, after she shared the story, um, you know, would she share it?

Uh, up to now she, she hasn't been able to do it.

So that's something that, there, there are still these hidden stories, um, with families, as much as we do.

Franklin: And there is a photograph that is profoundly moving, I think, of your grandmother, the mother of the soldier receiving a flag.

Ikeda: Yeah, there's so much in that photograph.

I mean, you know, historians, you know, love to look at photographs and the details.

And in that photograph, you know, my grandparents are on the left and there's a Japanese man on the right.

And you start asking questions, "So who is that?

And why is he there?"

Um, so I did a little more research, and there was no military official to, to give the flag, you know, to the family.

And so a Japanese immigrant ended up giving the flag, which, you know, I'm sure isn't Army protocol.

Furthermore, someone from the Army told me the fact that there was a piece of paper underneath the flag, you know, he said the flag should be pressed against the flesh.

That's the proper way to do it.

And so there's all these things that didn't happen.

And there's other photographs of that event.

And they're literally thousands of people on this dusty field in Idaho, probably, you know, a hot dusty day; it was in July.

Franklin: Yeah.

You can see people in the background looking.

Ikeda: And if you look in some of the, the, the photographs what's interesting, too, is in the very corner, you'll see some children just playing in the dirt.

And that's interesting for me too, because recognizing, depending on how old you were during World War II, was, you were impacted by the war.

And today we're still able to interview people who were incarcerated during World War Two, but they were children.

And so oftentimes the stories are so different.

They say, "Oh, you know, going to the camp wasn't that bad.

You know, we played, we had lots of friends."

But then you look at that and yes, you have children playing, but then you look at the faces of the first generation, you know, my grandparents' age, and just the, the hurt and sorrow in people's faces.

Franklin: How much had you known about Minidoka when you were growing up?

Ikeda: Actually very little.

Um, my parents would talk about other friends in the community as being in camp, and maybe being in this block.

I didn't really understand what that meant growing up.

And it really wasn't until high school.

When I started, uh, a teacher actually gave me a book, uh, it was a novel "No-No Boy."

She was a literature teacher.

And she said, so, you know, "Tom, you need to read this book."

And this teacher knew that I didn't know that much.

I mean, she was actually a Japanese-American teacher that was born in Tule Lake.

And so I remember reading that book and, um, and then going to my parents and asking lots of questions.

You know, my parents, you know, told me, or answered every question I, I asked, but you could tell they weren't really comfortable talking about it.

And so I just read more.

But, you know, it came really late.

I mean, I was what, 16, 17 years old before I really found out.

Franklin: Well, I think it's the same with Holocaust survivors and their families.

They just, they don't want to talk about it.

Ikeda: Yeah, I think they were trying to protect, protect me, and, and, uh, and not have us know that, you know, what they, they went through.

Franklin: Explain to people watching what the 442nd was and the fact that, uh, people were serving even when their families were also incarcerated.

Ikeda: Yeah.

So the 442nd was a segregated infantry unit, um, you know, with the Army.

Uh, at full strength, about 4,000 men.

And it was made up of the men, you know, sort of draft age men from both Hawaii and the mainland.

Through this mixture they were, they all were all brought together to Camp Shelby in Mississippi, where they trained and formed the 442nd, which then went on to Europe.

And their record of, of fighting was really unparalleled in U.S. uh, military history.

They are the most, or one of the most, um, decorated units for its size and length of service in our history, and, um, are highly regarded in U.S. military history.

Franklin: It's, it's still daunting for me to imagine, though, how these men and boys, because many of them were just teenagers, were, knowing that their families were in prison, still fought for the country.

Ikeda: And there was, and there were lots of reasons.

You know, I, I've mentioned, I've interviewed 250 people so far, and the significant portion of them were men who, uh, who came back.

And, and I, so I asked the question you know, "Why would you, why would you volunteer or fight for our country when your family is behind barbed wire?"

And it's a range of, of answers.

There were some who just felt it was their patriotic duty.

And they just said, you know, "I, I, you know, America is my country.

I just need to do this."

More, I think, um, believed that, they, they felt that if they did this, it would help other Americans see who they were.

And, and, by doing so, make it easier on their families.

Because they all felt that at some point they would be released from camp and families would return to their homes and they would have to deal with living amongst the general population.

And so they felt that if they could show how hard they fought for the country, that would be helpful.

Franklin: The whole language surrounding this issue has also changed.

The language was "evacuated to an internment camp" or "transit camp."

The language now is the use of the phrase "concentration camp, "imprisoned," "incarcerated."

Talk about that change in language, because of course the phrase "concentration camp" carries with it.

Ikeda: Yeah.

Franklin: .another meaning.

Ikeda: That's a great question.

When FDR signed Executive Order 9066, which essentially gave those military commanders to do anything in terms of rounding up anyone, they picked up 110,000 Japanese-Americans on the West Coast.

Two-thirds of them were U.S. citizens.

And they were given no, um, hearings.

There's no due process.

And they were placed in these concentrated areas.

And during the time, Franklin Roosevelt, other politicians, journalists, actually called them "concentration camps" during that time.

Um, and the way I view it is, you know, they're called concentration camps because these people did nothing wrong.

They were, they were, they weren't there because of anything they did.

It was, they were there because of who they were.

And that, you know, is technically the definition of concentration camps, so FDR and others were using it correctly.

It wasn't until later -- well, and then when the government started the whole, the whole program as our government will normally do, is they want to start using euphemisms.

And so rather than calling, say, a roundup, um, of, of Japanese-Americans, you know, they use the term "evacuation," which, which I've always learned and I think looking through the, the history of the term usually means that you're evacuating people to safety.

After the war, especially as, as we found out about the Nazi death camps, and, and the use of the term "concentration camps" to describe them, the use of "concentration camps" for the, for what held Japanese Americans, um, I think was stopped.

And people stopped using that.

And, but the historians sort of rediscovered that in the 1960s.

And so they've been consistently using it.

And I think, um, public historians and community organizations have all started adopting that because we feel like that's the better use of terminology.

Franklin: And I've heard it described that, um, the, the terminology that should be used for the camps during the Holocaust is "death camps."

Ikeda: Yeah, I think so.

I think "concentration camp" is a euphemism for "death camp" in that case.

Yes.

Franklin: Let's fast forward.

You you've been doing this for a quarter of a century, gathering these stories.

You've seen a lot of reporters like me come and go, um, asking you questions, doing pieces.

Uh, a man, well, I should back up.

You meet this man at an award ceremony.

You're both getting an award -- Daniel Brown.

Ikeda: Right, yeah.

Franklin: And, and, and he's famous for his book "Boys in the Boat."

And from this kind of chance encounter something grew and is now a book called "Facing the Mountain," which is, uh, selling well, I believe.

Ikeda: No, it is, yeah.

Franklin: Yeah, talk a little bit about this, um, synchronicity that happened that brought the two of you together to produce this book.

Ikeda: Yeah, it's, it's it's um.

Yeah, who would have thunk?

I think back it's now been almost six years.

Um, you know, a little sidelight.

So I, I knew Daniel James Brown was going to be at that award ceremony.

Um, I was being awarded, you know, for the work of Densho.

And I was a big fan of "The Boys in the Boat."

I'm a university of Washington graduate, uh, Seattle native.

So I, I knew about the Husky crew team.

And so I've always been a big fan of them.

And so when the book came out, you know, I read it.

And as a public historian, I loved it.

I mean, it's real history, but told in such an engaging way.

I think it's one of, um, the best examples of, of non-fiction that is just so interesting and readable.

And so it's one of my favorite books.

We chatted a little bit.

And then I finally said, and I, and "I like your book.

I mean, your book is just, just fabulous."

And he surprised me, actually, when he told me some things he knew about Japanese-American history and his family connection to Japanese-Americans in California.

And then he said, "And I'm actually really, really interested in the story, because I'm looking for, you know, a topic for my next book."

And, you know, having done this work and having worked with hundreds of filmmakers and authors and educators who have used the Densho materials, you know, I, I just saw this as a tremendous opportunity.

Because, you know, I thought that having someone like Daniel write the book would be, um, such a powerful, a powerful, you know, statement.

And, uh, and that began this relationship where I would send him some names and transcripts.

And, you know, our archive is all online, so he'd actually go online, do some searches.

And what I loved about Daniel is he, he would go through these interviews.

He's, he's very thorough, you know, he's a historian in his own way.

And he would then get even more information.

He would go out, contact the families, go to other primary source archives.

And pretty soon we're, we're just like two colleagues talking about the, you know, the people, the events, and going back and forth with ideas.

So it's been a really fun, exciting time for me.

Franklin: Was there any concern that it shouldn't be a white person writing this, that it should be a Japanese-American person writing this book?

Ikeda: Yeah, someone asked me that.

And I, you know, when I think about it, so the way I view this is the, the Japanese-American and what happened to them during World War Two is really a powerful American story.

And it should be written by the best writers, and the best filmmakers should be making movies.

And, and some of them will be Japanese-American.

Uh, so at Densho, and from my perspective, we work with everyone and, and it was, been a really an honor and pleasure working with Daniel.

Franklin: When you saw the book, what was your reaction?

Ikeda: Oh, it, it, um, so I, I read it with my daughter, um, who, um, was in Seattle at the time.

We got the advance reader's copy.

And I want to read it slowly, so we read it out aloud to each other.

Uh, it's, it's a pretty long book so it, it took us, you know, the course of a week.

Um, at nights we would read this.

And it's a great way to read the book, because, uh, Daniel's writing is, it's like a movie, I told him.

I said, "When I, when I, when I read the scenes, you can just picture it."

And by reading it that way, um, I was, I was deeply moved, and it was special to do it with my daughter, who's a filmmaker, too.

And, and she could see how moved I was at certain points where, you know, it was just hard for me to, to keep reading, because it was so emotional.

But she could also see how inspired I was because, you know, I, I told her as I was reading, "You know, these are men that I interviewed, I got to know."

Um, other than Fred Shiosaki, who was still alive at the point, the, the, the rest of them had passed away.

And it was such a, the, the book was such a way of honoring, you know, their lives.

And it just, it felt so special.

So, you know, I, I'm getting a little emotional now just thinking about, about what that book, that book was.

Franklin: What's your hope for this book?

Um, you know, as it moves through the world?

Ikeda: You know, one, that a lot of people will read it.

I think if people read it, um, they'll, there'll be changed.

Um, Dan, you know, talks about, yeah, we, we talk a lot about the world today and, and how to change people's, you know, thoughts about things.

And he talks about how you have to, you know, get them, you know, from the heart, and really get people to know people as humans.

And he does that so well in "Facing the Mountain."

And so if people could read this, especially people who, who don't think they want to know the story, this is the book for them.

My hope is, even going forward, that this book becomes, um, the foundation for perhaps a movie or TV series, also.

I think it, again, I talk about how cinematic Daniel's storytelling is, and I think filmmakers and others will see that and will use this to, to create other things from it.

You know, on a personal level, you know, again, talking about my parents and, and, you know, although they're, you know, 94 and reaching the end of their lives, I mean, just having these rich discussions about, about what, you know, this history is and, and, and feeling their, uh, what's the right word?

You know, maybe it's pride.

I mean, there's so happy that, that, um, I was able to do this, so it does feel good.

Franklin: Well, thank you very much.

Ikeda: Well, thank you, Marcia.

This was so much fun.

Franklin: I hope you've enjoyed this interview with Tom Ikeda, the founding executive director of Densho.

Our conversation was taped at the 2021 Sun Valley Writers' Conference.

My thanks to the organizers of that insightful event, to our guests, and to the Dialogue team.

If you'd like to watch this interview again, or any of the nearly 70 conversations I've taped at the Sun Valley Writers' Conference, check out our website.

Just go to idahoptv.org and click on "Dialogue."

That's also where you'll find a conversation I taped with Daniel James Brown, the author Mr. Ikeda helped with research.

For Dialogue, I'm Marcia Franklin.

Thanks for tuning in.

[MUSIC] Presentation of Dialogue on Idaho Public Television is made possible through the generous support of the Laura Moore Cunningham Foundation, committed to fulfilling the Moore and Bettis family legacy of building the great state of Idaho.

By the friends of Idaho Public Television, and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

With additional funding from the James and Barbara Cimino Foundation.

Dialogue is a local public television program presented by IdahoPTV

Major Funding by the Laura Moore Cunningham Foundation. Additional funding by the James and Barbara Cimino Foundation, the Friends of Idaho Public Television and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.