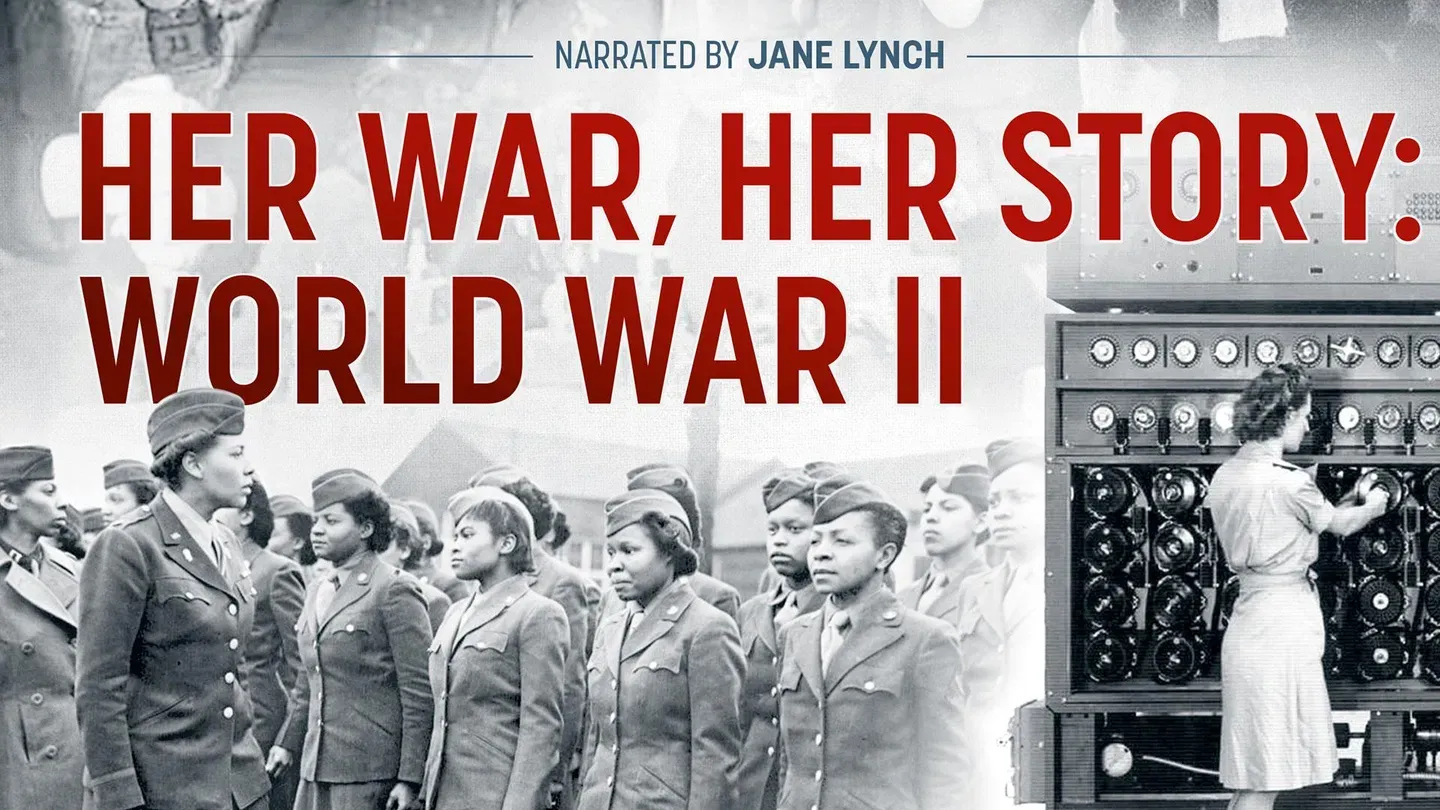

Her War, Her Story: World War II

Special | 58m 29sVideo has Closed Captions

The story of women in history’s most violent conflict, told by those who served.

Explore the stories of women caught up in World War II, from the American Home Front to Auschwitz Concentration Camp in Poland. Included in this hour-long film are also the personal stories of the incredible women who served in a war that proved women were equal to men when it came to patriotism, service, or in some cases, self-preservation during watershed moments which called for steadfastness.

Her War, Her Story: World War II is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television

Her War, Her Story: World War II

Special | 58m 29sVideo has Closed Captions

Explore the stories of women caught up in World War II, from the American Home Front to Auschwitz Concentration Camp in Poland. Included in this hour-long film are also the personal stories of the incredible women who served in a war that proved women were equal to men when it came to patriotism, service, or in some cases, self-preservation during watershed moments which called for steadfastness.

How to Watch Her War, Her Story: World War II

Her War, Her Story: World War II is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

♪ >> Funding for this program provided by... ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ >> Can looking back push us forward?

>> Ladies and gentlemen... Ms. Billie Holiday.

>> Will our voice be heard through time?

Can our past inspire our future?

>> ...massive act of concern.

♪ ♪ ♪ [ Applause ] >> From our farms and cities to the Great Lakes, WPS serves seniors across the country.

WPS -- serving our military and seniors since 1946.

>> For more than 25 years, Humana Military has cared for America's service members, their families, and their communities.

♪ >> Additional support provided by... ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ >> Too frequently, we're saying goodbye to the veterans and survivors of World War II, those who sacrificed so much in a global war for democracy fought on many fronts.

The stories shared from this war are often told by the men and boys who fought it -- from the generals to the GIs.

World War II's victory -- and in other nations, its defeat -- was also witnessed by and achieved through the extraordinary efforts of women, from the factories to the military bases and the home front.

It was also "Her War and Her Story: World War II."

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ >> General Eisenhower said the Army needs and can use all it can get.

Who are the women who will help retain the needed manpower for the production battle at home?

Who are the women who will help fight our country's war?

>> We are in the machine shop, in the repair shop.

We rig the parachute.

We guide our fliers home.

>> At air bases here and overseas, women soldiers perform over 25 technical jobs.

Ladies and gentlemen, General Marshall.

>> The Women's Army Corps is an integral part of the Army of the United States, and its members, who are soldiers in every sense of the word, perform a full military part in this war.

There are hundreds of important Army jobs which women can perform as effectively as men.

In fact, we find that they can do some of these jobs much better than the men.

As more and more American soldiers engage the enemy in combat, women must replace them at overseas bases and at posts in this country.

>> Everybody was doing something.

Everybody was happy to do something.

They wanted to do things.

It was the most patriotic time I have ever lived through.

>> We had to help.

I mean, that was it.

That was our goal.

>> It had a great feeling for me that I was doing something worthwhile with my life.

>> During the last two weeks in August, the German armies move toward the Polish border, where they assemble 70 divisions, many of them armored.

>> On September 1st, 1939, Adolf Hitler's invasion of Poland was the spark that ignited a world war in Europe.

Just two years later, Japan attacked the United States' Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

After that, America could no longer sit on the sidelines of this global conflict.

>> No matter how long it may take us to overcome this premeditated invasion, the American people and their righteous might will win through till absolute victory.

[ Cheers and applause ] ♪ ♪ ♪ >> Even as President Roosevelt's words echoed across the radio, hundreds of thousands were already signing up for what was now indeed a global war.

Patriotic teenage boys and young men headed off to training, preparing them for the war in the Pacific and Europe.

But who would now step into the shoes of these new American soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen and produce the tools of war needed to defeat the enemy?

It would be the same people who had been doing it in England since 1940 -- millions of women.

A comparable outcry was now coming from the United States.

"Train us to do the work.

Give us the opportunity.

Allow us to help win this war."

Like their English counterparts, American women were not allowed to serve in actual combat.

But they found their footing during the Second World War in the factories or on the home front.

Hundreds of thousands of women also put on the uniform in military-support roles.

>> It was hard talking about it.

It was almost like it was a forbidden subject, and I should never talk about it.

So, plus, in the meantime, it was easy to keep it a secret because nobody asked.

Nobody remembered that sort of thing.

For years and years, it wasn't even discussed.

>> Satisfied they had created the right sense of fear in the world, the Nazi leaders were now ready to strike.

The hour had come.

It was time to start conquering Eastern Europe.

>> Long before the United States ever thought of getting involved in another world war, Adolf Hitler's Germany was already quietly killing tens of thousands of people in Europe.

In the 1930s, Germany's Nazi Party targeted Jews, gypsies, homosexuals, political adversaries, and the disabled for death, all part of Hitler's plan for a master race.

Irmgard Schmid was a schoolgirl in Germany and witnessed the rise of Nazism.

>> Opposite the church was a synagogue.

And it was, you know, all the doors were boarded up, and the Jews had sort of disappeared.

There were none in our school anymore, no Jewish schoolchildren, you know?

And they were by that time wearing yellow stars.

♪ ♪ >> Those wearing the yellow Stars of David were destined for concentration, or death, camps with names such as Treblinka, Dachau, Buchenwald, and, eventually, Auschwitz.

♪ ♪ If you were young and non-Aryan in the late 1930s, a slave-labor camp was most likely your first stop in Germany.

Anna Arbeiter, Jewish, ended up at one in Poland.

The Nazis planned to work the teenager to death.

>> I came in to Starachowice.

They put me in the kitchen.

You know, to work.

We did the tables.

We washed the dishes.

We cleaned.

I cleaned the room for the Germans, you know.

And I helped them out.

I worked there maybe for, I don't know, a half a year.

>> Meanwhile, for German schoolgirl Irmgard Schmid, life under Nazi control was part of her daily routine.

German propaganda was everywhere.

>> I was nine years old.

Uniformed men came to our school and put up posters of -- inscribed posters saying, "Die Juden sind unser Unglurk," meaning "The Jews are our downfall."

>> Everyday Germans were training to become hardcore Nazis, especially young boys and girls.

Parents were blamed if a child resisted.

>> I was a Hitler Youth, but not by -- so much by choice.

You had to, every teenager.

Everybody had to join it.

It was automatic.

You had no other choice.

But it was not a bad experience because we went on field trips, almost like the Girl Scouts here.

Its purpose was very similar.

>> Irmgard Schmid was aware enough to understand what was going on but had to fall in line with her schoolmates.

>> There were propaganda stories that during the war, Germany became happier.

The German population became happier.

♪ People were yelling, screaming, "Heil Hitler" and "Down with the Jews" and "Die Juden sind unser Unglurk."

I had information coming from all sides.

There were the posters.

There were the soldiers coming in and saying, "Germany is the greatest, the best, the finest."

And our beloved fuhrer, Adolf Hitler... [ Speaking German ] You know, stuff like that.

And I heard my father talk in whispers about how bad Hitler was because he was after the Catholics.

But often my father was drunk when he said these things.

So, there was a measure of suspicion about him, as well as everyone else.

>> It was safer to stay quiet and go about your daily lives.

Subservience kept you alive.

>> My father was not a Hitler sympathizer, but he did work for the government because he had a business, and he had to deliver.

I mean, he made -- the factory made batteries, car batteries, and he had to deliver to the military.

He made money on that, but he had to deliver to the military.

>> Adolf Hitler's all-out attack on Poland makes the long-dreaded European war a certainty.

>> On September 1st, 1939, Hitler's invasion of Poland brought about a declaration of war by France and Great Britain.

World War II was under way.

>> Up to the very last, it would have been quite possible to have arranged a peaceful and honorable settlement between Germany and Poland, but Hitler would not have it.

>> By 1940, the Germans had conquered the majority of mainland Europe.

England was alone to fight on.

With most of Great Britain's soldiers retreating in Europe, fighting the Nazis in North Africa or the Japanese in the jungles of the Pacific, the Germans began an effort to bomb England into surrender.

It was called the Blitz.

>> For 28 days, the Nazis were to drop everything in the book on the city of London -- tons upon tons of high explosives.

>> I remember the day the war started.

I remember the prime minister spoke to us.

>> I expect that the Battle of Britain is about to begin.

Upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilization.

>> My mother walked in the bedroom and said, "Take your gas mask.

Here's a candy bar.

You have to go."

And I said, "What did I do?"

And she said, "Nothing.

You're being evacuated."

>> It was unbelievable to them that there was going to be another war.

And they were just -- people were really scared at the time.

>> Right away, the same night, no lights.

There was -- all streetlights, everything.

We had to have windows absolutely with dark curtains so that no light came through.

Anything going over -- no aircraft would see a speck of light that they would see that his was an area where they could bomb.

>> I can remember the starting of the bombing of London.

I mean, I remember the Blitz.

The first bomb actually dropped in London -- not in London, in the outskirts of London September the 4th.

>> Germany's air attack on England lasted almost a year, from September 1940 to May 1941.

The German Air Force, or Luftwaffe, targeted most major British cities, especially London.

16,201 women died, along with 18,629 men and 5,028 children.

England never surrendered.

>> I was 14.

I just had my 14th birthday.

>> The London Blitz -- I mean, it came for London just about every night, every other night, or every week.

>> I was evacuated into the country to a place that I would have dreamed I would have loved.

It was called a manse.

I hated it.

In three months, my friend and I got on a bus and went back to Southampton, and that was the end of our evacuation.

♪ >> British spirit was certainly tested between the Blitz and several early defeats in World War II, but England's resolve never broke.

There was no better example of this than during May 26th to June 4th, 1940, at a beach on the northern French coastal city of Dunkirk.

In what's called the Miracle of Dunkirk, England managed to evacuate an incredible 300,000 of its surrounded soldiers from the beachhead there, along with many French fighters.

The British Navy proved heroic in ferrying the men back across the channel to safety.

But hundreds of civilians, using their small pleasure boats, aided in the incredible evacuation effort, too.

>> We were close enough to hear the guns and hear the noise, and we all understood that all the little boats were going out to pick up the people.

>> German anger intensified after the embarrassment at Dunkirk, with more nightly bombing raids on English cities.

>> The night the house got bombed, I was at the end of the air-raid shelter, which was about this long, and the sack did this, and the earth kind of came in.

And it was the only time in my life that I truly thought, "I'm going to die right now."

>> My mother and grandmother went into the country.

We had a cottage down there.

And they and my aunt and her two daughters and my younger sister were down there, and my mother said she can remember so clearly the night they bombed Coventry.

And that was when 2,000 bombers came over from -- it was a constant stream of bombers going over.

And of course in the morning, there was nothing left.

There was not a stone upon a stone left in Coventry.

>> The biggest thing for me in the war was the noise.

Everything was noise, it just seemed like.

And, of course, you know, everything that came down from the sky made a different kind of noise.

And that was probably the scariest thing.

>> Across the channel, the enraged Goering took personal command of the operations.

>> With World War II now raging on several fronts, Jewish teenage slave laborer Anna Arbeiter arrived at the Nazis' most infamous death camp, Auschwitz, near Krakow, Poland.

Her future husband, Izzy, was also there.

Auschwitz, a combination of three separate camps, had one purpose -- to murder people.

At its peak, some 10,000 prisoners a day were gassed, shot, and cremated -- Jews, gypsies, Russians, political detainees, and other undesirables.

Nobody knew their fate upon arrival.

Everyone tried everything to stay alive.

>> And every time, when I would clean the tables, I asked the German, the big shots, Herr Becker, whether we can take the food that they left, like rolls.

They didn't touch it.

You know, some food, not what they eat.

Some things, you know?

And he said to take it because I wouldn't do it, you know.

>> As Anna Arbeiter searched for her next meal and tried to stay useful to the Germans, women in England continued mobilization for the war effort.

The Blitz seemed to be over.

British women could not fight in actual combat, but that didn't stop them from joining branches of military service early in the war.

Soon enough, their resolve and patriotism would prove a model for women in the United States.

>> Everybody in England had to register between the ages of 16 and 45.

And so, you had a choice.

They would call you up.

You're conscripted, drafted.

And you had a choice of Army, Navy, Air Force, or nursing.

I was in the Ordnance Corps at first, stationed in Derby, going through everything.

And then I got orders through the officer, and I was transferred down to the south of England, Chelmsford, where I had to go to a technical college and learn how to become a welder, which I did.

They call them "fusion engineers."

>> They work full-time, overtime, 40 hours a week -- 50, 60, 70.

>> Had some kind of bad experiences working on the tanks in that times because they'd come back from the front, and the tracks didn't smell too good when you... And, of course, sometimes you'd look inside and find things that... were not very nice.

So, what they did in the end in the REME -- it's the Royal Electrical, Mechanical Engineers -- they made up these mobile workshops, like, big eight-wheeler, and everything was on there, from lathe operator to welding, everything.

So, they would take them out into France instead of bringing the stuff back.

♪ ♪ >> War rationing also became the norm in Great Britain, as it would soon in America.

Securing just the basics became a part of everyday British life.

>> We were rationed.

You had two ounces of butter, two ounces of lard, two ounces of margarine, a pint of milk -- this is a week -- and 12 ounces of meat.

But it was a time of when we're all worked together.

We were fighting for one cause, to get rid of somebody that was doing a lot of harm in the world.

>> In the fall of 1941, frustration grew in Great Britain as the English soldiered on alone against the Germans.

Nerves were fraying.

>> And pretty soon we were a little bitter because the Americans weren't joining in.

But pretty soon, they joined in.

The next thing you know, the Yanks are coming.

We were told you must not date Americans because they're oversexed, overpaid, and over here.

I like to think I had been around the block a time or two.

So, the first American I met, I told him that.

It didn't mean what they meant.

It just meant we had seen a lot of life.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ >> Before the Americans ever arrived in England, there was, of course, December 7th, 1941.

The Japanese sneak attack would launch America into the Second World War and a two-front battle.

Barbara Kotinek's dad worked at Pearl Harbor.

On December 7th, the 6-year-old had a front-row seat to the entire Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

>> The morning of the bombing, basically, the noise woke us up.

The planes coming over the Navy housing, they were coming over to go down into Pearl Harbor, and they were shooting.

Then, we went outside to see some of the neighbors were gathering.

And one of the neighbors had a shortwave radio and said the Japanese were bombing us and attacking us.

♪ ♪ My dad said he could see the metal.

He said, "This is the real thing."

Sometime within that week, he took me down to the harbor and drove me all through the shipyard, showing me the devastation.

And there were patrol boats out in the water.

I asked him -- they were small, little boats -- and I asked him what they were doing.

And they had -- the guys in the boats had long poles.

And he said they were pulling bodies out of the water.

And he said to me, "Don't ever, ever forget this."

>> On the mainland of the United States, the Japanese strike on Hawaii was also about to change the life of Julia Parsons.

>> I heard that Pearl Harbor had been bombed, and I had no idea where Pearl Harbor was.

I had never heard of it.

I had no idea it would have such a tremendous impact on my life.

>> When the war first broke out, I was too young.

But my brother, my cousins, my whole family went in.

But the women, we had to be 20.

We released the guys so they could go and fight.

And that's what they told us.

We're taking the place of the men to win.

>> ♪ This is the Army, Mr. Jones ♪ ♪ No private rooms or telephones ♪ ♪ You had your breakfast in bed before, but you won't have it there anymore ♪ [ Horn blows ] >> After basic training, millions of American men headed east towards North Africa or Europe or west for the South Pacific.

So, who would now work in the factories building the planes, jeeps, tanks, and trucks, and producing guns and ammunition for the fight?

American women, of course, so-called "Rosie the Riveters."

Quickly, the efforts of these female workers would reach across all facets of war production, from rudimentary tasks to confidential projects.

>> One day I was walking by the employment office in Waltham.

I lived in Waltham when I was working at Raytheon, and they had a notice in the window that a man would be coming up to search for employees for the shipyard, people that would like to start working there, producing their products there.

And one of them would be welding.

You know, not Rosie the Riveter exactly, because we're not putting rivets in ships at that time.

Probably they were a few years before.

So, I decided I'd go in and talk to the man.

And, sure enough, he talked me into applying for a job in five minutes.

I went to the floor of a shipyard, and they said, "We'll send you to school three days.

You'll learn how to weld overhead, vertical, and horizontal," which I did in three days.

[ Laughing ] Graduated with honors.

Then I went out on the water to work, and I worked everywhere -- the superstructure, in the engine room, ICC room, welding all by myself for eight hours a day.

[ Laughs ] But, you know, we were very fortunate.

We had the materials in this country to work with.

We were very fortunate.

And we did have all these women available.

>> X-ray technicians, inspectors of Army meat, teachers schooling our soldiers... >> Across the United States, women mobilized for the war effort.

As the fighting progressed, and the Allies made gains in the Pacific and Europe, some factory work became top secret.

>> I didn't know what they were used for till they told us.

>> Therese Ricard was only 16 years old when she took a job at the U.S. rubber plant, painting Sherman tanks made entirely of rubber.

>> They told us that was in place of real tanks, but that didn't register.

>> Long after the war, Ricard would discover why the military wanted fake rubber tanks.

It was for a top-secret D-Day deception plan.

>> You didn't want the boys to go over there and get killed.

But a lot of them did.

>> When you went home at night, you knew you were going to return the next day, and hopefully you were going to help save someone's life.

You had that feeling always with you when you were working.

>> As the war continued, the Allies' drive for victory picked up momentum, in large part thanks to those American and British women in factories turning out the guns, ammunition, vehicles, and record numbers of bombers.

Thanks to those Rosie the Riveters, American and Allied air forces now had the resources to strike critical German cities day and night.

>> The bombings, that was the worst part.

Munich was almost half-destroyed -- the bombings.

And we went -- I worked for my father in the office, and he says, "You cannot leave until all the books are in a vault."

You had one of those -- and the bombs were already flying.

One time I end up in a basement with my father, and he says, "As long as you hear them, they're not hitting us.

They're not hitting us."

I says, "Well, what about the ones I don't hear?"

-- you know, hitting us.

It was not -- it was terrible.

I was laying on my knees.

I says, "I'll do anything, anything you want me to do.

Just make all this stop."

It didn't matter who was winning, who was losing, and any of this, see?

♪ ♪ >> Many British and American women not in the factories decided they wanted to serve in uniform.

Though they couldn't fight, they each felt they possessed individual skills crucial to the waging of war.

More than 350,000 enlisted in female-only branches of the Army, Navy, Coast Guard, Marines, and Air Corps in the United States alone.

They went by the acronyms WACs, WAVEs, SPARs, and WASPs.

It didn't matter if they were black or white.

>> Someone suggested to me, "Why don't you join the service?"

This was something fairly new.

>> During World War II, the American military was segregated for both men and women.

That didn't stop Deloris Ruddock from joining the first and only all-black-female battalion in the Women's Army Corps.

The 6888 Central Postal Directory battalion included five companies, totaling about 850 black women.

>> We were working three shifts a day, you know?

So, that was it.

And we got the mail out, sorted it out, and directed it to where it was supposed to go.

Those soldiers who were deceased, sent them back to the States or to the family.

Those who were on duty, mailed it to them.

>> The mail was sorted.

You could tell who was gonna get what mail and whatever.

>> Anna Mae Robertson also signed up with the 6888.

Their unit wound up in France, moving all the mail that kept soldiers on the front lines in touch with family back home.

>> We got the job done.

>> Getting the job done was a common goal for American women during the war years, no matter where the job took them or their assignment.

>> We danced every night with soldiers, many of whom were very poor dancers.

And the phrase I shall always remember is we had to dance every night.

And we were working 7 days a week, 12 hours a day.

>> You see these young kids come in messed up.

It's horrible.

I think anybody that actually was in the front lines doesn't like war.

I think everybody who is there, we felt good about what we did, but, at the same time, we thought, "What a waste."

>> We'd have to get up early in the morning.

And I mean early.

And then we'd go march and jujitsu.

When I left the basic, they transferred us to Boston army base.

That was military police.

And it was tough.

And we had to guard the prisoners of war.

I get a laugh from it, yeah.

When I think of it today, how dangerous.

Prisoners of war would come in.

It was tough, but we did it.

We had a club.

We had the phone.

And we had our own sentry box, you know?

Four sentry boxes, four girls, like, you know, in each one.

>> All the boys in my class in college were long gone.

ROTC took off immediately on graduation.

>> Julia Parsons had perhaps one of the most top-secret assignments of any American woman in World War II.

>> I saw in the paper that they were accepting women in the Navy for the first time.

The midshipmen school was Smith College in Northampton.

It was beautiful.

It was strict.

We were treated just like the men were.

We marched everywhere.

We had to wear our uniforms at all times.

There was no civilian clothes allowed.

It was a 3-month course in communications, they called it.

But the only communications we did was in the field of the radio, Morse code, transmitting messages.

[ Morse code tapping ] I don't really know how I was assigned to Washington, D.C.

They just gave us our orders, and we followed them.

We were all put in a room, and someone came in and said, "Does anybody know German?"

And I said -- I raised my hand, and I said, "I had two years of it in high school," and that was it.

I was the only one who had had any German, so they immediately shipped me to the section called "OP-20-G," which was the German submarine traffic.

We were not all sent to code-breaking places.

There were many who went to Washington, who went to other divisions of the Navy.

>> Not every servicewoman in World War II had a top-secret job like Julia Parsons' Enigma code-breaking assignment.

Most women contributed in their own way.

Those who worked in the factories or a branch of the military felt they positively impacted the war effort in some manner.

>> I was a wacky WAC in the Women's Army Corps.

And when I enlisted, signed up, I wanted to be a driver of some big shot and work in the motor pool.

But all I had was secretarial training, so they stuck me in the secretaries' pool.

>> Alba Thompson's job was far from the routine.

It was history-making.

Thompson found herself out in the Pacific working on the staff of one of World War II's most famous leaders, General Douglas MacArthur, commander of all forces in the Far East theater of war.

>> General MacArthur was a man who, when someone recommended me for a promotion, said, "What has she done?"

This is me standing in the room, you know.

I wanted to fall through the floor, of course, since this was the wrong way to do all of that, of course.

And the State Department man who recommended me said, "She is a superior officer," with which General MacArthur replied, "I don't have any other kind.

What else has she done?"

[ Chuckles ] But that was -- there was no quarter given as to what your sex was or what your background was.

You just were expected to work and to work at a very high level.

But he had the same standards for himself, and General MacArthur was forever the polished general officer who brooked no interference.

He required the highest kind of work ethic and creativity, too, if that was ever in the books.

And he -- I don't ever recall him making a personal remark to me that indicated I was the only woman on his staff or anything of that kind.

>> Douglas MacArthur recognized Alba Thompson's brilliance.

[ Tapping ] ♪ As a code breaker, Julia Parsons had the same experience.

The military, it seemed, did not discriminate when it came to brainpower or talent.

As in Great Britain, in America, it was liberating to be a part of something much greater than oneself.

Women like Julia Parsons had a role in saving lives and winning the war in Europe.

That's all they asked for in World War II -- the opportunity to help.

>> I have no idea how the Navy or anyone else picks a code breaker.

I guess you have to have a mathematical mind because the mathematics does come in there and certainly into the Enigma machine.

The section that I was in did the German submarine traffic only, the U-boats they called them.

England had gotten so overwhelmed that they finally asked if the United States could take part of the code work, and they were happy to do it.

And we did.

All of the units at the communications annex used the Enigma machine.

>> Parsons' work as a code breaker had the highest clearance possible.

>> Very top secret.

We were threatened with everything under the sun if we ever divulged anything.

The posters would say, "Loose lips sink ships."

And that was the motto to go by.

Just don't say anything at all.

And we didn't.

My primary job was to learn how the Enigma machine worked.

It wasn't a very big machine, but it did have a standard keyboard, and it had four rotors, which we called "wheels."

The code of the day had what was called a wheel order.

This was changed every 24 hours.

And the setting on the wheels was changed every 12 hours.

So, the code was fundamentally only good for 12 hours.

And then we had to work on it again to get the other 12 hours of the day.

The alphabet lined up from "A" to "Z" on both sides of the wheel.

When you pushed the keyboard letter, it came up as perhaps an "E," but it would never come out as an "E" because a letter could never be itself.

And this went in, then, the next wheel as a letter and came out another letter and another letter for all four wheels.

And with each stroke of the keyboard, the wheels rotated one time.

Sometimes they rotated twice.

It was just about as safe as a machine could be.

We got all of the radio messages from all over the North Sea, Europe, and then tried to decide what they were saying.

We would run what we thought the message said below the code itself, and if anything crashed out, if the letter came under a letter, we knew that it didn't say that.

Then you'd move the code words that we thought it said.

We'd move it over one letter and try it again and another letter.

If we got a whole line of perhaps 26 words, 26 letters, that would be enough to make a crib to make this menu.

These numbers then were put into the computers that we had in the basement of the building.

This was the computer that Alan Turing and his crew put together.

Nobody in our group knew everything, but we did get to go down and see the machine at one point.

But the numbers were put into the computers, and the computer would spit out every possible wheel order that could produce those numbers.

And then we would get the numbers back in our office, and they would be tested to see if they were coming out in German.

Most times, of course, they did not.

But when we got one that did come out, we had broken the traffic for that morning or afternoon or whatever.

>> Even after the war ended, the Germans still had no idea that the Allies had found a way to decipher their coded Enigma messages.

>> We knew their tricks.

You always used a dummy word first, and you always made it a different length.

And you always left a few spaces and threw in something that was not important.

What made it easier for us to break the code was the U-boats appearing on the surface to recharge their batteries.

And during that time, they had missed all the control's messages that came, and they would then radio back to control and say, "I have missed messages," say, 289 through 314.

The only ones they repeated were the important ones.

We knew they were the same message that we had broken the traffic for two days before.

So, that was easy, then.

And they got careless in repeating that.

They should not have used the same message exactly worded as it was.

But they did.

And when the German sub skippers wired back to control, saying, "I think they're reading our messages.

Every time I wire control for missed messages, within a half-hour there's a plane overhead."

And Admiral Doenitz, who was the head of all German control, kept saying, "No, impossible.

They could not possibly read our messages.

They cannot read the Enigma machine."

It was frustrating when we couldn't break the code, but we always assumed that if we couldn't do it, the next watch could.

Well, we did finally break the day's traffic.

We were just so excited.

It was almost like Christmas for us when things did work out.

>> H-Hour, and the enemy's hedgehog defenses are ahead.

This is the supreme moment of invasion.

This is frontal assault on an entrenched enemy.

>> Just as British women had endured the Blitz in the early days of the war, those civilians living in Western Europe had the fighting brought home to them, too, on many occasions, none more impactful than on June 6th, 1944, in northwest France -- D-Day.

Remember Therese Ricard and those fake rubber tanks?

They were part of a ruse in England.

A fake army led the Germans to believe the Allied invasion would come at Pas-de-Calais, France, the closest point between Great Britain and France.

Instead, the attack came further south, in Normandy.

The D-Day invasion was horrific for those civilians living on the coast there, especially behind Utah Beach.

>> We had the feeling we were going to die.

The next shell is going to hit us, and we're going to die.

We would have stayed in the house, but it was crumbling all around us.

All the plaster, all the windows crumbling and smashing.

We couldn't stay in the house anymore, so we decided to move outside to a trench that belonged to another family and to be together there.

>> We prayed all night.

It was shocking.

Everything was moving in the house.

The earth was shaking from all the shelling.

We were right in the middle of the battle.

We could hear the bullets passing everywhere.

>> Many of the enemy troops didn't know what hit them, and the cooperation of the French aided our cause.

>> Despite D-Day success and victory in Normandy, Julia Parsons and her female code breakers weren't done with their Enigma code-breaking assignment.

>> Toward the end of the war, when the Germans knew they were losing, they got very careless.

And that was one of the ways in which we finally did finish the German submarines.

♪ ♪ ♪ I don't know how the rest of the girls feel about all of this, but I felt very personally connected to some of these people because we had been trying to get their submarines for a long time, and they were all cleverly dodging our efforts.

But there's one thing about sinking a submarine, and there's another thing about killing people.

And the killing people was what I felt really bad about.

But, nonetheless, it was there.

And I guess that is war.

I know that's war.

And it was -- I felt very, very, very badly about the one who had just had a son, and his submarine was sunk.

And I thought that son will never see his father.

And it was just a very poignant feeling, which, of course, nobody else talked about.

Nobody got any special credit for this.

We got a unit citation at the end of the war, but that was just our little section of it.

But due to the nature of our jobs, we weren't allowed to publicize that.

It was not a matter of reward.

We just wanted to break that code.

And it was a fixture in our minds.

♪ ♪ >> Throughout the world, throngs of people hail the end of the war in Europe.

>> World War II finally ended in Europe on May 8th, 1945.

Germany, like most of Europe, was in ruins.

>> After the war is over, you felt relieved, relieved from everything, and happy, actually, that we made it.

I mean, my whole class, in schools, died.

My uncles, my cousins -- some of them in Russia, some of them in France, and some of them underneath, underground.

Practically my whole family was wiped out, yes.

>> For some women, World War II introduced them to their future husbands.

These so-called "war brides" came from all over Europe and followed their new husbands back to the United States.

>> We got married in 1944.

And we were interviewed.

We had to wait six months.

But I got married in three months because I got papers to move out.

I was being transferred.

So my husband went to his office and asked special permission, and he said to him, "Is she pregnant?"

He said, "No, she's been transferred."

And so, I was transferred down to the south of England, and he put in a request to have me stationed within five-mile radius of his camp, which was allowed at that time.

Your family or your brothers couldn't be in the same camp, but, you know.

So, they transferred me back to Chilwell, Nottingham.

>> For many who survived, their World War II experience would leave emotional scars and severe guilt that would never go away.

>> In 1949, as a young girl 18 1/2 years old [sighs] to work as a servant maid in Jewish households in Paris -- that's what I wanted.

I wanted to do penance.

Sometimes it was penance, and sometimes it was redemption.

And after many years of both, after three or four years of working in England and in France... to do my stint there, I didn't feel guilty about it anymore.

>> As is the case with the veterans who fought, those women who survived the world's most horrific event can't ever forget World War II.

For some, whether they lived or died depended on luck.

The memories, scars, and sometimes tattoos carved into their skin at places like Auschwitz will never disappear.

>> Once in a while, I see it.

I sleep.

I see something, you know?

It comes mind as the house where we lived.

I wouldn't say that we were millionaires.

We were, you know -- two rooms, seven kids, and our father did good.

I come from a nice family.

Everybody were poor in Poland.

There were no rich.

There were maybe.

There were rich people, not many, you know?

They worked hard, and they'd come to this, and... and for no reason.

Because you're Jewish?

Look at that.

I came in to Auschwitz.

They start to yell in German.

At least German I understand a little.

Sometimes, it comes back everything, yeah.

And, you know, when we came in, we had to take off the clothes.

They tell you to pick up the hand -- 14-year-old girl.

They start to shave, you know, with that.

They shave up my head.

I had no hair.

In Auschwitz I had no hair.

In Bergen-Belsen, my hair start to come in a little bit.

And we took, you know, a piece right there and just covered up.

And that's it.

And she -- one grabbed this hand and one is this hand.

They put the needle in, and that's it.

And I looked around, and I said, "I would be better off maybe to go with my parents."

You know, they were dead, yeah.

I didn't believe that I'm going to come out.

Never.

And I didn't care.

♪ ♪ >> On September 2nd, 1945, World War II officially came to an end, with the unconditional Japanese surrender on the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

♪ By then, some 60 million people were dead, both soldiers and civilians.

Like everyone else, the women of World War II were caught up in the events of that time.

They, too, returned home and went on with their lives, part of a generation, both male and female, who answered the challenge of preserving democracy.

>> Oh, I look back with great pleasure.

I loved being in the service.

It was thrilling.

It was really nice.

Everyone thought I had a desk job, which I did, but it was not a desk job as they had in mind.

And that used to hurt the ego because you knew what they were thinking.

But that was the way it had to be.

I think it's interesting that the country came together as a whole, in spite of the fact that half of the people detested FDR.

But they followed him.

They backed him.

They pushed everything.

They did everything they could.

Everybody did.

It was just a fantastic time in our history and probably the most exciting part of my life.

>> Well, when I come home, like, you know, my cousins from New York and all, they all came down to my house and all that, you know?

It was a terrific feeling.

>> Code breaker Julia Parsons never spoke about her job until just recently.

She kept her pledge of secrecy for decades.

Only when her work was officially declassified did she start to share her story.

>> I finally told my husband one night when we were all sitting out on the patio with some neighbors, and he asked me, just the neighbor asked me what I had done during the war.

And I thought, you know, it's been so long, and it was almost like it was a forbidden subject, and I should never talk about it.

I didn't know that it had been declassified, for one thing.

Nobody ever let us know.

And I asked somebody in the Navy that I knew.

I said, "Why did they not tell us?

Was this ever in the papers?"

They didn't have any idea about the papers or why it wasn't announced publicly.

But they said that the Navy keeps no track of where anybody is, so they didn't know where anybody was to let them know that they could now talk about it.

>> One of millions of women who lived through the war or played a role in securing eventual victory -- her war... her story... World War II.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ >> Funding for this program provided by... ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ >> Can looking back push us forward?

>> Ladies and gentlemen... Ms. Billie Holiday.

>> Will our voice be heard through time?

Can our past inspire our future?

>> ...massive act of concern.

♪ ♪ ♪ [ Applause ] >> From our farms and cities to the Great Lakes, WPS serves seniors across the country.

WPS -- serving our military and seniors since 1946.

>> For more than 25 years, Humana Military has cared for America's service members, their families, and their communities.

♪ >> Additional support provided by...

Her War, Her Story: World War II is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television